ONLINE BROCHURE

Points of Interest

special places along the route

Points of Interest

Click + below to READ more information

1 | Cleora Townsite

Cleora—A Railroad Town That Never Matured

Once a growing town filled with promise, Cleora stood just east of the junction of CR105 and US50, near both the beginning or the end of the Stage and Rail Historic Route. In the late 1870s, Colorado’s railroad industry here was a battlefield, with two major companies—the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) and the Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG)—locked in a high-stakes race to lay narrow-gauge tracks from Cañon City to Leadville. The challenge? The hazardously narrow Royal Gorge could accommodate only one rail line, and the courts were to decide which line got the go-ahead.

Confident in its success, the AT&SF secured land from a local rancher (Bale—see POI 3) and ambitiously mapped out the town of Cleora, attracting hundreds of eager settlers who saw it as the next great railroad hub. But fate had other plans. In 1879, the courts sided with the D&RG, granting them exclusive rights to build the railway. Instead of running tracks through Cleora, D&RG chose to establish its own town just a few miles away, a settlement originally called South Arkansas—now known as Salida.

The impact was swift and decisive. One by one, Cleora’s buildings were abandoned, its residents packing up and moving themselves and their buildings north to Salida. In just a few years, Cleora became little more than a ghost of its former self, its dreams of railroad glory vanishing into history.

Fast-forward to 2025, and Cleora has been reborn—not as a railroad town, but as a modern spectacle of minimalist living. Today, it boasts one of the largest Tiny Home developments in the United States, with approximately 200 homes redefining the landscape. Yet, echoes of its past remain. Across the river, south of US50, the historic private Cleora Cemetery still stands as a quiet reminder of the town that once was.

For those intrigued by Colorado’s rich and complex railroad history, there’s no shortage of stories to uncover. Books like Colorado Midland Railroad: Daylight Through the Divide by Dan Abbott, Tracking Ghost Railroads in Colorado by Robert Ormes, and Colorado Midland by Morris Cafky delve deep into the dramatic battles and engineering feats of the era. And for a quick reference, a condensed summary is available as you travel along the Stage & Rail Historic Route, helping relive the past as you journey through this remarkable landscape.

2 | Cleora Stage road Bridge

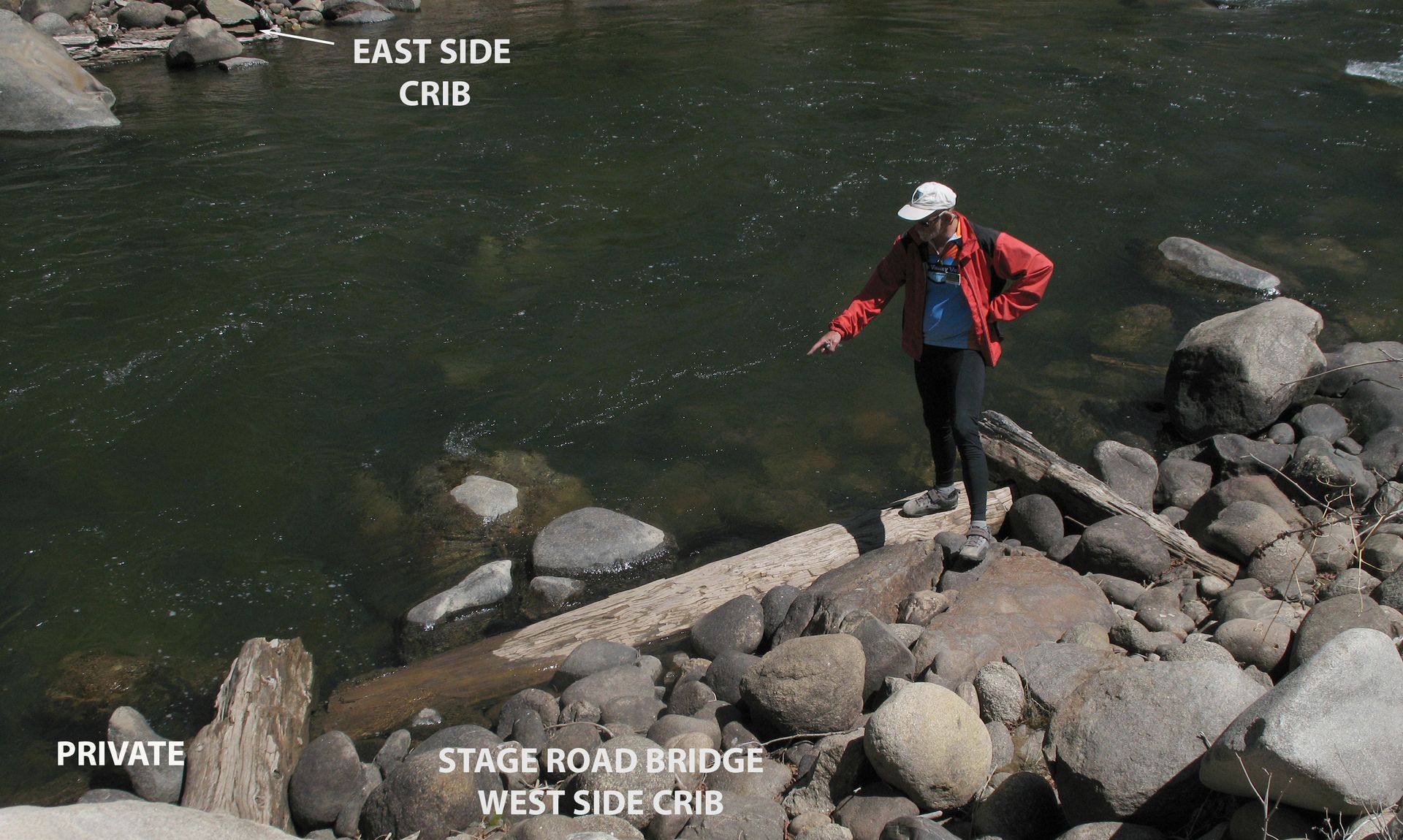

The Stage Road Crossed the River at Cleora

Cleora’s story (POI 1) is of a bold but fleeting endeavor. Established by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF), it briefly thrived on the north/east bank of the Arkansas River on land purchased from rancher William Bale (see POI 3). At the time, the stage road wound its way up the river along that same side, making Cleora a strategic choice for a future railroad town.

But even before Cleora’s short-lived rise, Bale had already staked his claim on the region’s future. He built a stage station hotel on the south/west bank, knowing that weary travelers would need a place to rest, and coaches needed a change of horses. To ensure a steady flow of stage traffic—and to connect with what would become Salida—a bridge was built, linking the two sides of the river. It’s not clear exactly where the bridge was located but its east end was likely south of the area now occupied by the Salida Sewage Disposal Plant.

Though Cleora faded quickly, and the bridge is long gone, its legacy lingered. Even into the early 1900s, old-time Salida residents recalled stories passed down from their grandparents—of walking or riding horseback across the Cleora Bridge to attend the town’s brief but still-functioning school. These whispers of the past still echo through the landscape, reminding us that history is never truly lost—it simply waits to be rediscovered.

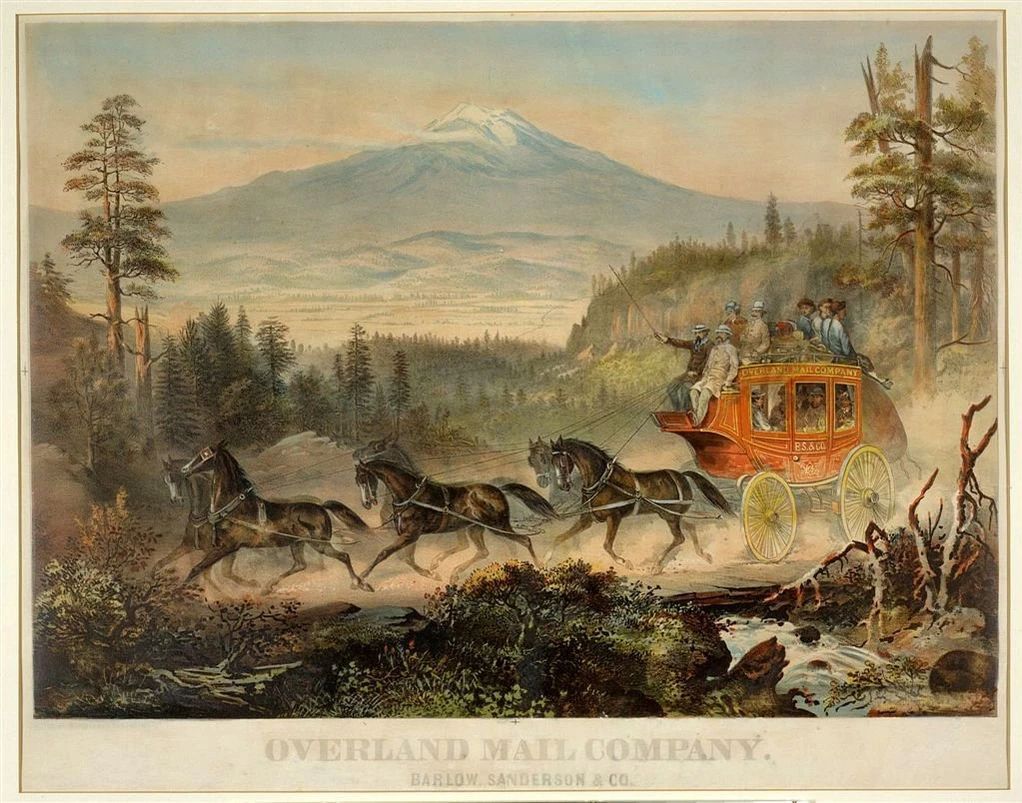

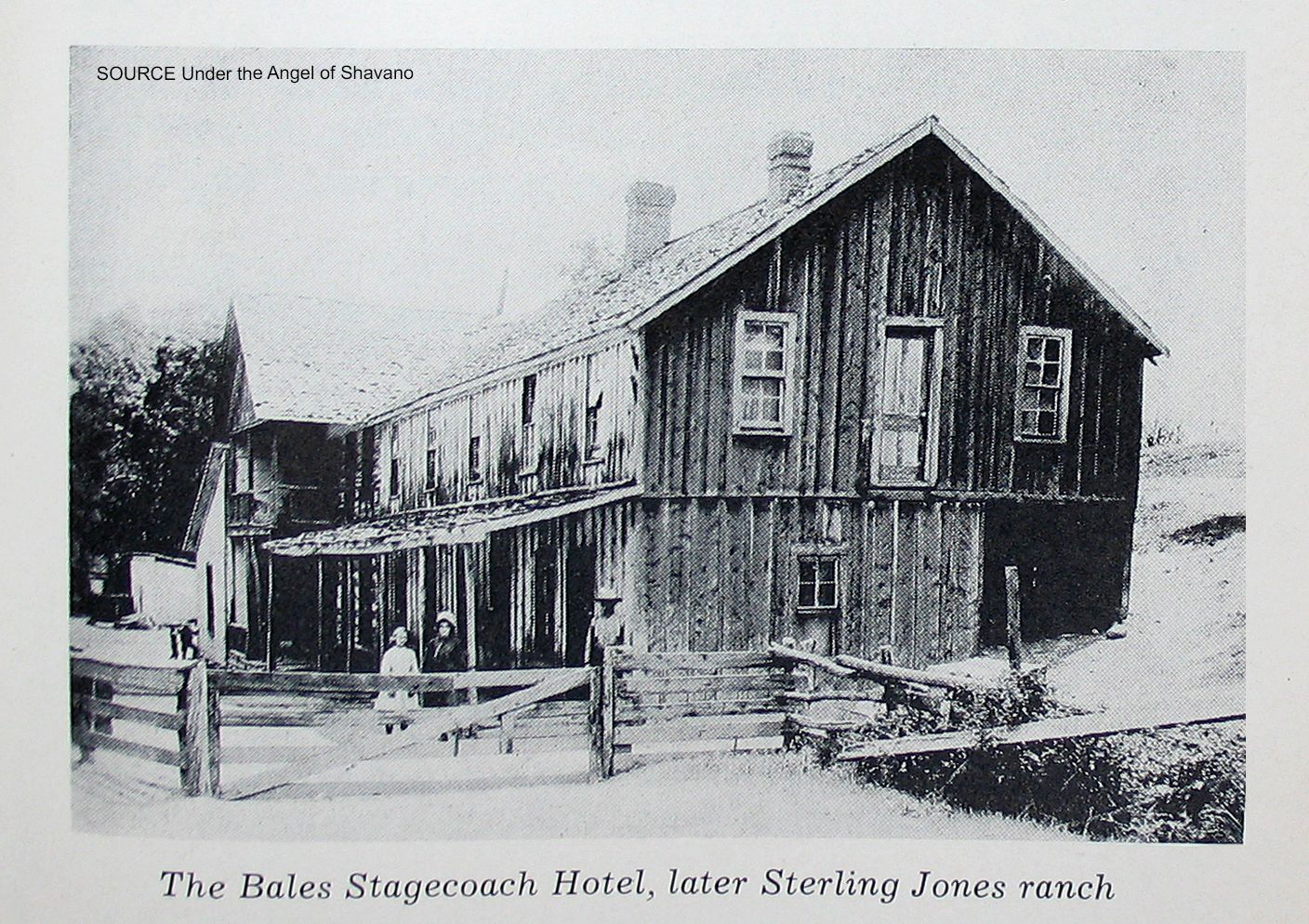

3 | Bales Stagecoach Hotel

The Bales Stagecoach Hotel: Stage Stop and Local Tavern

By the mid-1870s, when William Bale purchased ranch land on both sides of the Arkansas River—just south of what is now Salida—the Cañon City to Leadville Stage route was just beginning to function. Recognizing an opportunity, Bale capitalized on the increasing stream of weary travelers by establishing a stage stop complete with a hotel, stables, and a barn at the confluence of the South Arkansas and Arkansas Rivers.

For passengers who had already endured hours of bone-jarring travel from Cañon City, the Bales Stagecoach Hotel was a welcome sight. Many spent the night recovering before continuing the exhausting journey to Leadville. Meanwhile, just across the river to the east, Bale sold land to the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF), which briefly gave rise to the town of Cleora—named after one of Bale’s daughters (see POI 1).

Until the early 1880s, when Salida—originally known as South Arkansas—established its own stage station and hotels, Bale’s hotel was the area’s primary hub for travelers, merchants, and locals alike. More than just a resting place, it became a lively social center, where news was exchanged, deals were struck, and friendships were forged.

Bale himself grew into an influential local figure, respected for his business acumen and community leadership. However, his legacy carries a darker edge—he was also believed to have been involved in the infamous Lake County War, a brutal and lawless conflict over land and water rights. This violent dispute saw vigilante justice take a deadly turn, with several extra-judicial killings, culminating in the murder of a judge inside his own courtroom in Granite while attempting to prosecute the perpetrators.

Although Bale’s stage stop and its original structures are long gone, the echoes of his enterprise and the dramatic events of those days still linger, reminding us that history here was shaped as much by ambition and innovation as it was by conflict and controversy.

4 | Historic Railroad Hospital

Salida’s Railroad Hospital and Historic Buildings

In 1880, the Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG) Railroad finally reached Salida, bringing with it a wave of new residents and railroad workers. Recognizing the urgent need for medical services, the company soon established the Denver and Rio Grande Hospital. For decades—until 1962—it remained under D&RG management, providing care primarily for its employees. When local community leaders purchased it, the hospital continued as a private institution until 1976, when it became part of the Salida Hospital District. Eventually renamed the Heart of the Rockies Regional Medical Center, it served the community in its original building until 2008, when it moved to a modern facility on Salida’s western edge (see POI 12). Today, the historic railroad hospital lives on as the Tauber Building, Salida’s City Hall and administrative hub.

Downtown Salida itself boasts a storied past, particularly within its downtown Salida's Historic District—recognized on the National Register of Historic Places since 1984. More than 100 buildings make up this district, most fashioned from local brick and originally designed as commercial or residential spaces to support the rapidly growing railroad town. As you follow the Driving Route, you’ll pass several of these heritage buildings, now repurposed into shops, boutiques, restaurants, and even an events center within the lovingly restored Salida Steamplant.

For a deeper dive into Salida's history—150 years of characters, conflicts, and triumphs—consider a brief detour to the Salida Museum, just off US50. Whether you explore the exhibits in person or browse their online resources, you’ll find a trove of stories that bring to life Salida’s colorful past and vibrant present.

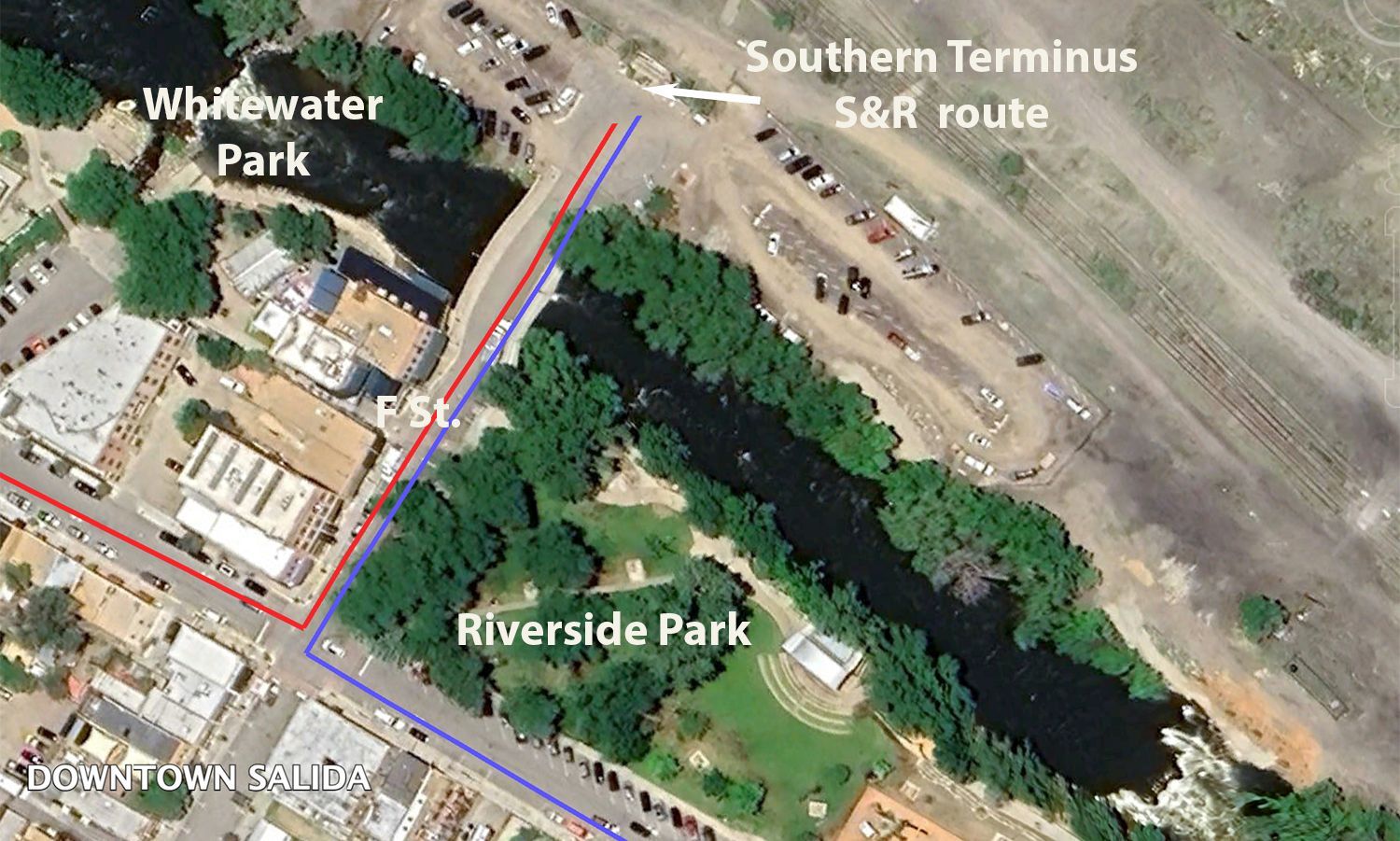

5 | Riverside Park

Salida’s Cool Popular Downtown Parks

Riverside Park and the river trail is Salida’s most popular and heavily used green space. Usually quiet and peaceful, with tree lined trails and picnic tables, it also hosts busy concerts and festivals. It is adjacent to Salida’s regionally well-known and challenging Whitewater Park, centerpiece of the 77-year old Fibark Whitewater Festival.

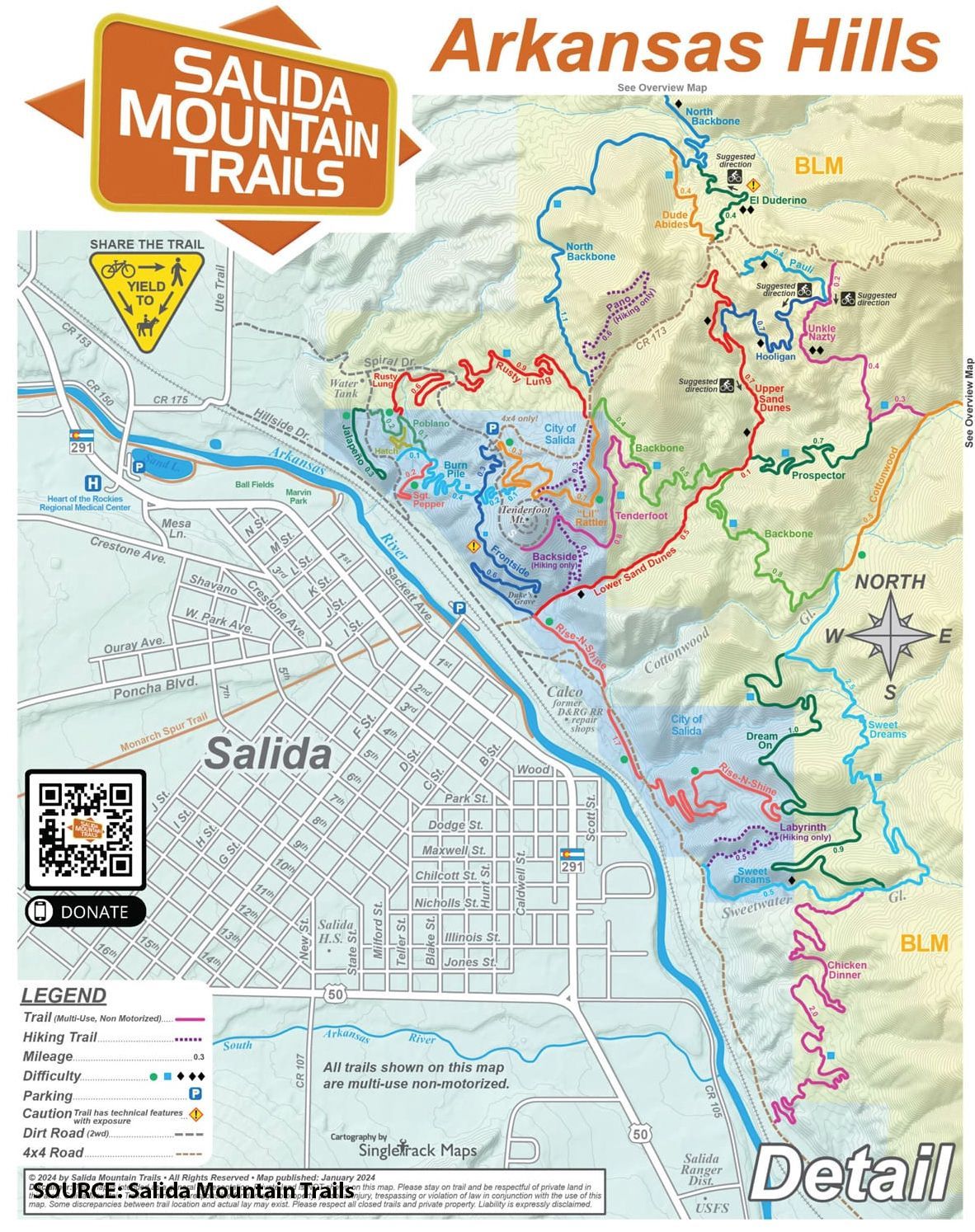

6 | Southern terminus of the S&R - Info

A Starting Point

For those embarking on the Stage and Rail Historic Route, the journey officially begins at the north end of the F Street Bridge in Salida. While the route technically extends several miles further south to the junction of CR105 and US50, this spot at the bridge serves as a convenient starting point. A map of the entire route is displayed here, and with reliable internet connectivity, it’s a good place to download resources that may be unavailable along the way. You can also access an audible tour of the Salida to Big Bend section to enhance your experience.

In addition to being a gateway to history, this location is also the trailhead for the Arkansas Hills Trail System, an extensive network of pedestrian and mountain biking trails that weave through the rugged terrain on Salida’s S Mountain and beyond. Whether on foot or two wheels, the trails offer wonderful views and a chance to survey the landscape that shaped the pioneers and rail workers of the past.

A Vision Years in the Making

The Stage and Rail Historic Route wasn’t developed overnight—it is the result of years of careful planning, research, and community involvement. Detailed insights into the project’s journey can be found on the S&R website, where you can explore the 2012 Feasibility Study and 2015 Draft Master Plan under the "Dig Deeper" section.

The project’s dedication to interpreting history while creating an attractive recreational experience has not gone unnoticed. In 2013, American Trails, the nation’s largest and most prestigious trail support organization, honored the S&R project with its national Planning/Design Award. This recognition was based on the Feasibility Study’s innovative approach, strong public participation, and cost-effective integration of existing trails and roadways.

A Record of Recognition and Connections

The recognition didn’t stop there. In a highly competitive selection process, the S&R project earned a place among Colorado’s Top 16 Trails, as part of the Colorado the Beautiful Program, championed by then-Governor John Hickenlooper. Competition for this status was intense, with scores of applicants. The successful 16 projects ranged from constructing new trail routes to expensively filling gaps in on-going long distance trail work along the Front Range and I70 corridor. The S&R project, with the lowest anticipated costs for implementation, was deemed worthy largely because of the extent of its public involvement, partnership support, and incorporation of existing trails and slow speed county roads.

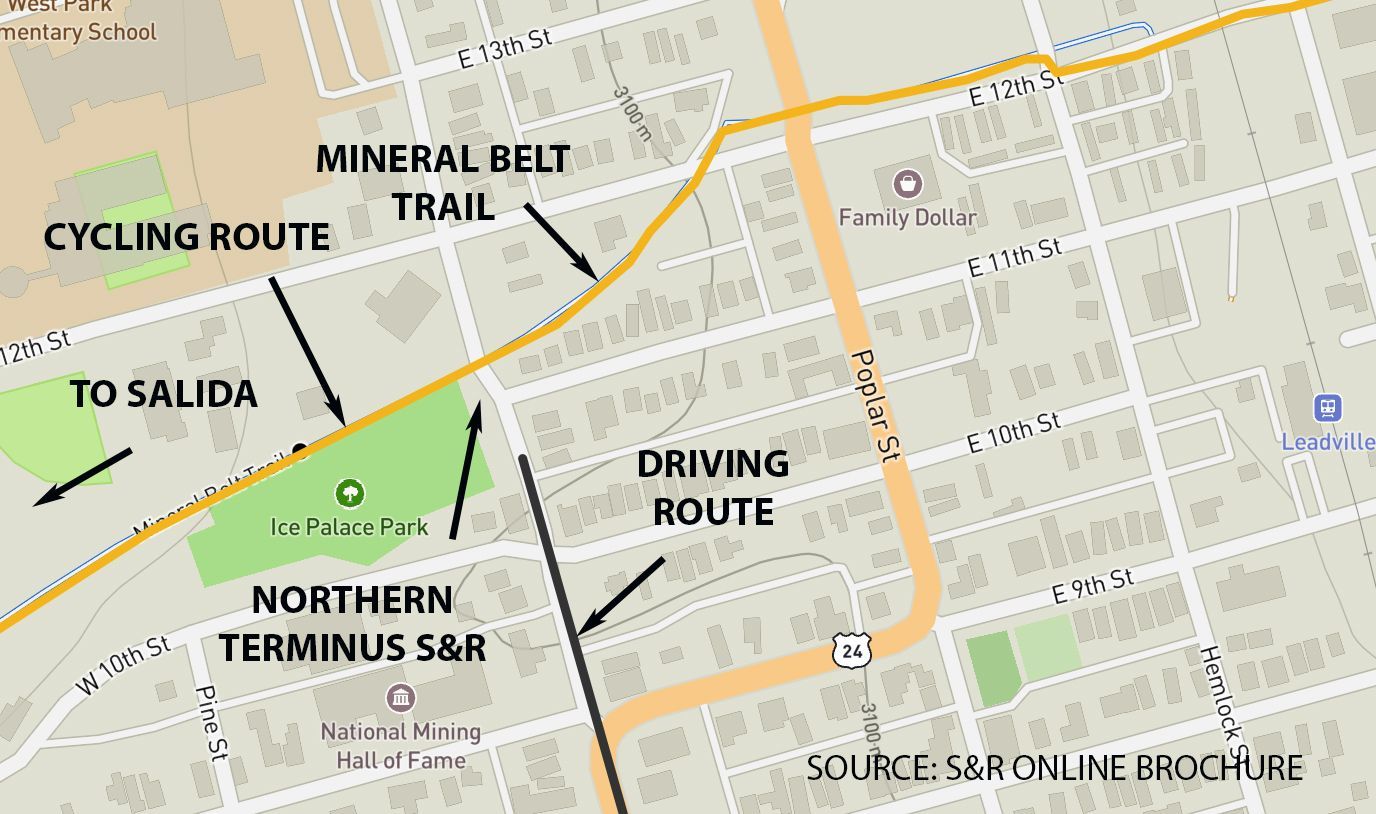

The Fremont Pass Recreational Pathway (POI 56), another Top 16 project, shares a connection with the Stage and Rail Route. Once completed, this sophisticated paved trail will stretch from Leadville over Fremont Pass to Copper Mountain independent of the existing highway. By design, the S&R historic route’s northern terminus is essentially the southern starting point for the Fremont trail.

With history underfoot and adventure ahead, the Stage and Rail Historic Route is more than just a path—it’s a living story waiting to be explored.

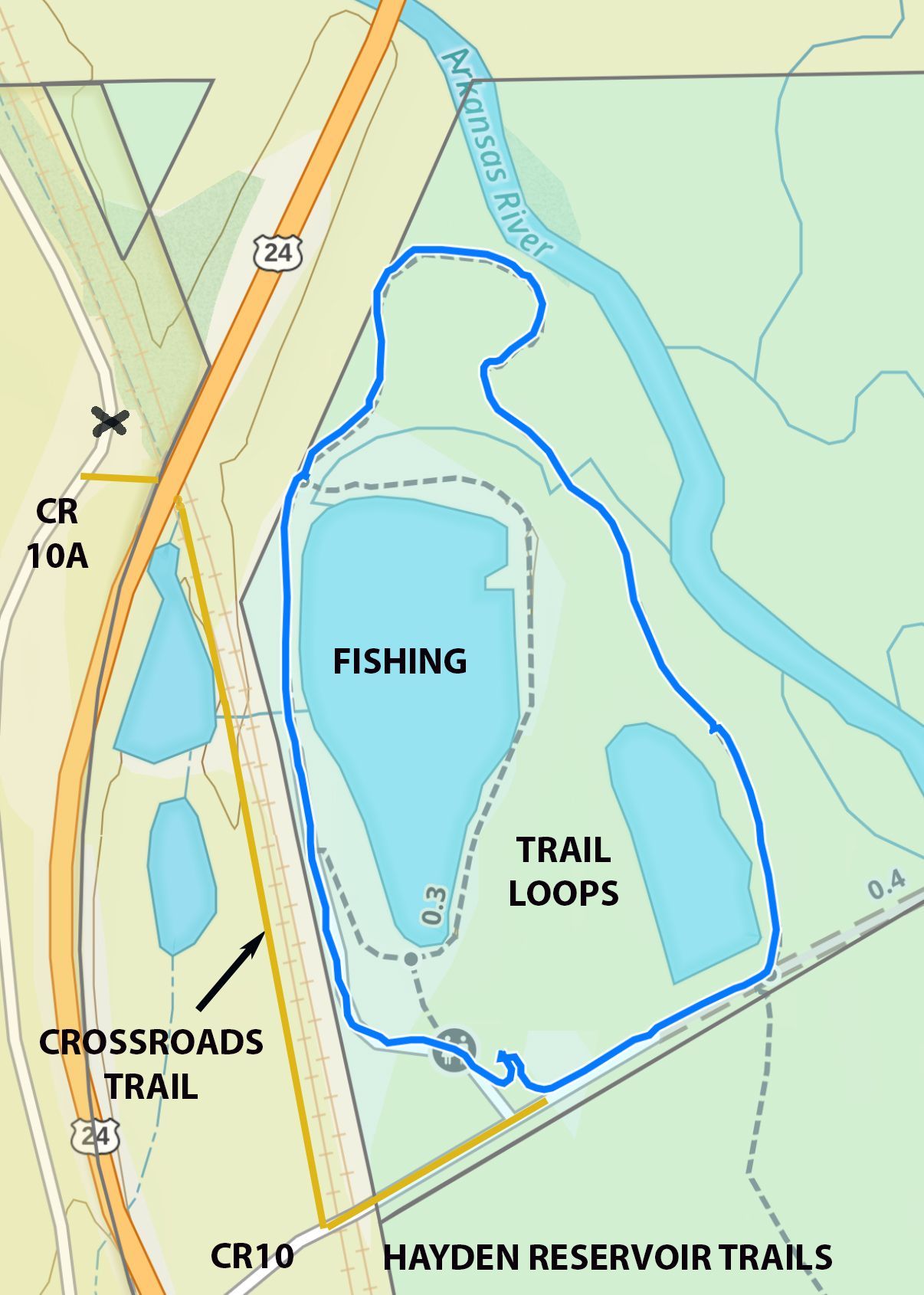

6A | Trail along Arkansas River/Marvin Park

Incorporating Salida’s Town Trails and Parks

Marvin Park is popular because of its baseball diamond but also for its beautiful riverside walking and cycling trail, part of Salida’s town trail system, which the S&R cycling route follows. Cyclists can take advantage of the map to proceed to POIs at Sands Lake and the Obelisk. Sands Lake and Marvin Park are also accessible from the driving route. Salida is home to other city parks, walking trails and a hot springs pool.

7 | Sands Lake

A Pause for Birdlife: Sands Lake

Sands Lake is a State Wildlife Refuge and is open to fishing but also known for its diversity and abundance of water birds. It typically rates at the top of sites surveyed in the annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count for the number of different species observed in a single sample day. Salida is fortunate to have it within its city limits. It can be accessed from either the driving or cycling routes.

8 | Border Obelisk

Marking an Unmarked Past: The 2014 Obelisk Project

In 2014, an evocative art project emerged from a museum in Guadalajara, Mexico, aiming to shed light on a nearly forgotten chapter of history. A team of Mexican and American artists collaborated to place 47 symbolic obelisk-shaped markers along a boundary that was once set in ink but never marked in reality—the 1821 border between the United States and Mexico.

This border, defined by treaty when Mexico gained independence from Spain, was short-lived. In 1848, after the U.S. emerged victorious in the Mexican-American War, the treaty was rescinded, and Mexico was forced to surrender 55% of its territory to the United States. Some historians describe this as a "land grab disguised as a war," forever reshaping the map of North America.

By placing these silent obelisks along this invisible, erased border, the artists sought to spark a conversation about the magnitude and consequences of that conflict. The markers stand as both memorials and provocations, challenging viewers to reconsider the past and its lasting impact on identity, land, and sovereignty.

What if that original boundary had remained? What histories and cultures might have evolved differently? The obelisks, standing in places where a line was once drawn and then erased, invite us to ponder not just what was lost—but what might have been.

Unfortunately, vandals appear to have recently removed this thought-provoking display. The Buena Vista obelisk also was removed, but fortunately was retrieved and is in safe keeping at the Heritage Museum.

9 | Mt Shavano Fish Hatchery

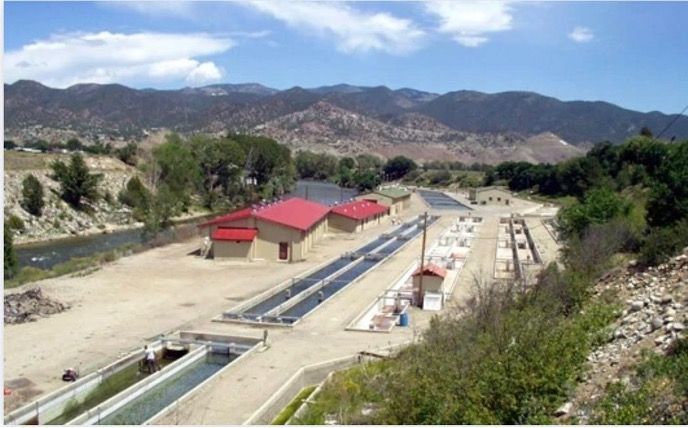

Colorado’s Historic Fish Hatcheries

Established in 1956, the Mt Shavano State Fish Hatchery, managed by Colorado Parks and Wildlife, remains one of the largest fish hatchery facilities in the state. It produces hundreds of thousands of catchable-size, disease-free trout and millions of fingerlings, which are released annually into Colorado’s cold-water streams and lakes. Tours are available but must be arranged in advance.

Farther north, the Leadville National Fish Hatchery, located just off the S&R driving route in southern Lake County, is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Established in 1889, it is the second oldest federally operated fish hatchery still in operation today.

10 | Franz Lake

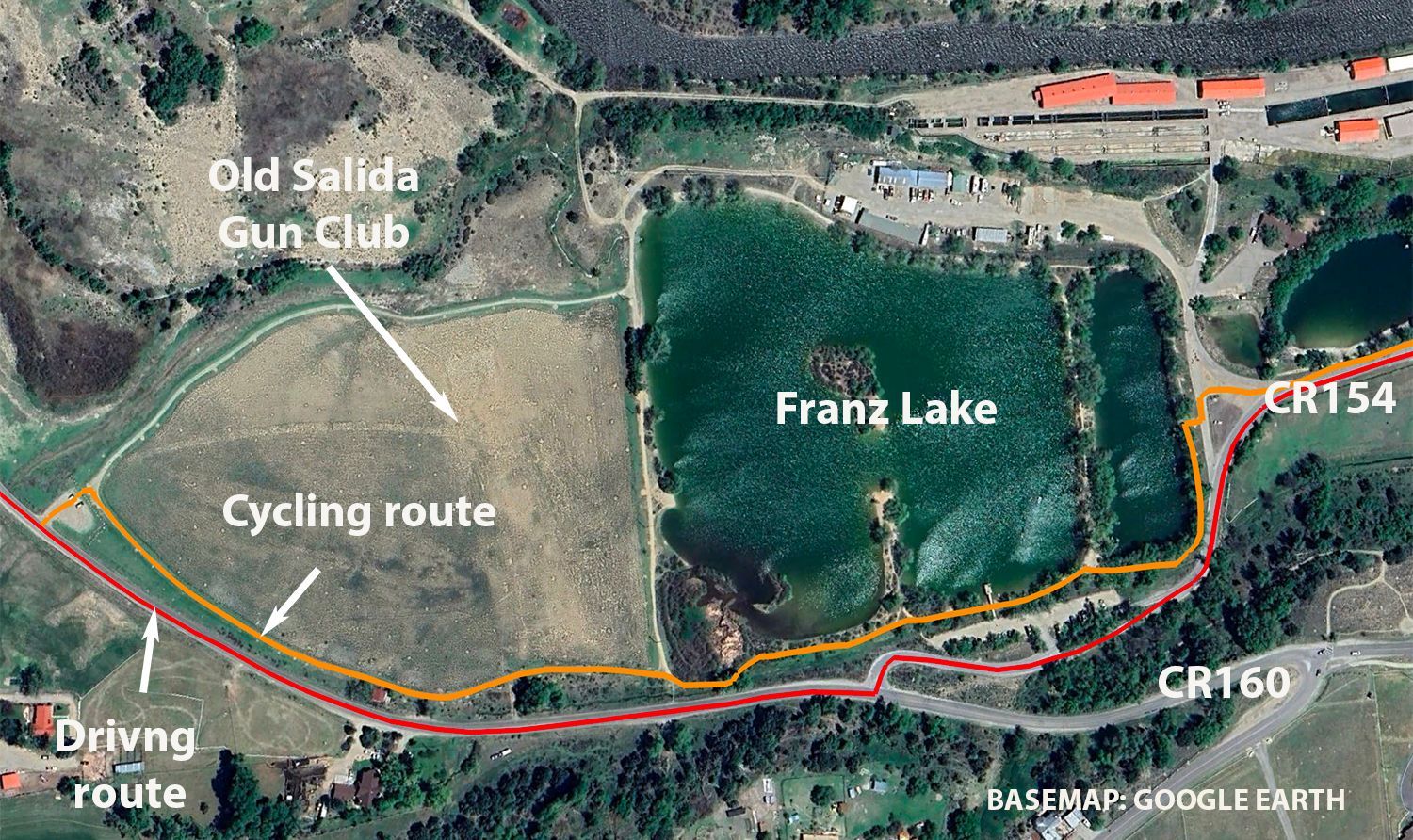

Frantz Lake State Wildlife Area – A Fishing Hole Near Salida

Frantz Lake State Wildlife Area is a top-quality fishing lake located just west of Salida. It provides a high-quality fishing experience for the whole family and features an ADA-accessible fishing pier.

While motorized boating is not permitted, the lake is perfect for hand-launched fishing craft such as canoes and kayaks, making it a popular spot for anglers and paddlers alike. A loop trail circles the lake, which cyclists on the historic cycling route could add into their ride as an extra.

11 | Salida Gun Club Trail

Cyclist’s choice west of Frantz Lake

Cyclists and pedestrians can continue through the Frantz Lake parking area to a trail that traverses the old Salida Gun Club (see next POI). The backdrop is a classic view of several of Colorados’ 54 14,000 ft mountains (“14ers”). Most prominent is Mt Shavano at 14,228ft with Tabeguache Peak (14,155ft) behind it and Jones Peak (13,604ft) to the north.

12 | Salida Gun Club Story

Land Swap for the Future: How a Gun Club helped build a Hospital

Salida’s Heart of the Rockies Regional Medical Center (HRRMC)—a state-of-the-art medical facility—might never have existed in its current location if not for an unlikely land exchange with the State of Colorado and the Shavano State Fish Hatchery.

The story began in 2003, when the City of Salida sought to trade its abandoned Salida Gun Club property for state-owned land suited for a modern hospital. However, there was a major obstacle: decades of gun club use had left the land seriously contaminated with lead shot and other toxic metals, making it ineligible for exchange.

That’s when the Greater Arkansas River Nature Association (GARNA) stepped in, leading a coalition of partners—including the city, Chaffee County, and external grant funders—to clean up and restore the land. Using a mix of grant money, city and county-provided labor and heavy equipment, contaminated soil was capped and, in some cases, removed. By 2004, the land was deemed safe for transfer, clearing the way for the State’s Shavano Fish Hatchery to accept the exchange.

With this newly acquired site, HRRMC launched an ambitious, multimillion-dollar project to build a regional hospital capable of serving Salida, Chaffee County, and parts of neighboring counties. Just five years later, the doors to the leading-edge medical facility opened, radically improving and transforming healthcare access in the region.

Since then, HRRMC has continued to expand, with major additions completed in 2019 and further developments already in the works. What began as an abandoned gun club, written off as unusable, became the foundation for one of the region’s most critical medical institutions—a credit to community collaboration, environmental rehabilitation, and forward vision.

13 | Salida Smelter Smokestack

The Legacy of Smeltertown: Industry, Impact, and Restoration

To the northwest of Salida, a massive lead and zinc smelter operated from 1902 to 1920, employing thousands of workers who lived in the bustling community of Smeltertown. Raw materials arrived by rail from as far away as Leadville and closer mining districts, fueling a major industrial industry that played a crucial role—especially in producing metals for World War I armaments.

Although most of the smelter and town has long since disappeared, one towering smokestack remains, preserved thanks to passionate local support. You can explore more about its history on the Salida Museum website. However, the smelter’s success came at a cost. For years, byproducts like slag were “conveniently” dumped along the nearby Arkansas River, contaminating the shoreline and potentially the river itself. The problem only worsened when a creosote factory treating wood products and railroad ties later moved in, further polluting the area with heavy metals and toxic chemicals.

By the early 1990s, the 120-acre site had clearly become an environmental hazard. Recognizing urgent need for action, the EPA designated it a Superfund site, launching an extensive cleanup effort from 2000 to 2004. Crews removed contaminated material, capped hazardous soil, and drilled deeper freshwater wells to provide safe drinking water. Since then, experts monitor the site with onsite evaluations every five years.

To learn more about the cleanup process, visit Smelter Superfund cleanup.

14 | Poor Farm

The Poor Farm – An Historic Evolution in Function

The Poor Farm began its long history in 1892 on 100 acres of land extending down to the Arkansas River in the north. For nearly 50 years, it served as a refuge for the poor and destitute of the county.

In 1940, as social services became available elsewhere, the Poor Farm closed its doors and remained abandoned for forty years until an initial restoration in 1982. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985 following that restoration. Unfortunately, it fell into disrepair once again—until privately purchased in 2017, and underwent yet another restoration.

The Poor Farm is now a private residence, not open to the public.

Please respect private property here and elsewhere along the historic route.

15 | River and Mountain Views

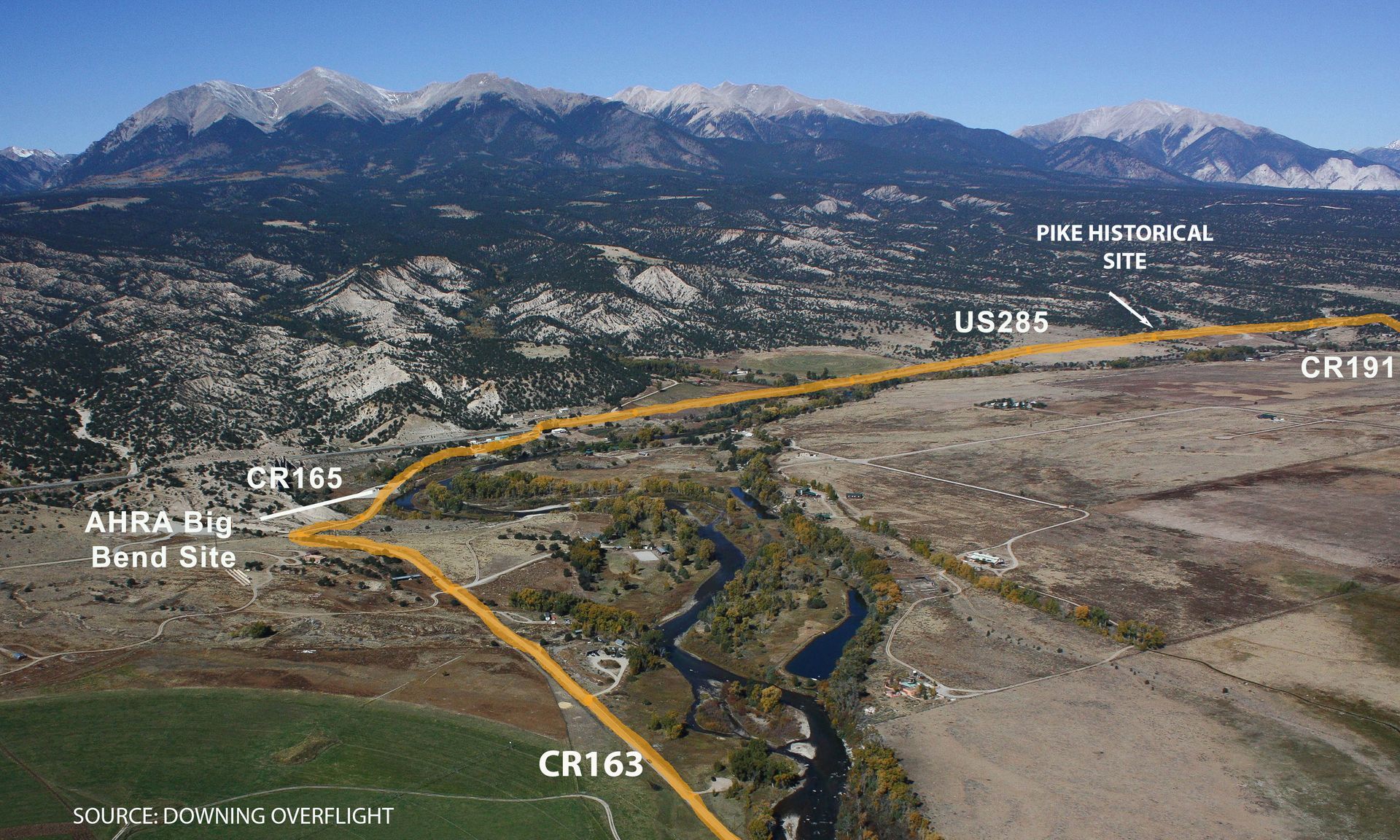

Scenic & Historic Exploration on CR163

The S&R driving route on CR163 offers a smooth and scenic ride along a well-maintained gravel road with minimal traffic—perfect for both vehicles and cyclists, including mountain and gravel-grinding bikers. This section can be the beginning of a longer or even a full through-route experience or a rewarding out-and-back morning ride.

Steeped in history, this route closely follows the path of the 1870s stage road that once connected Salida to Buena Vista and Leadville. As it winds through the level uplands and historic ranchlands, travelers are treated to spectacular views of the Arkansas River’s more tranquil stretches and towering 14ers like Mt. Shavano.

Whether you're exploring on four wheels or two, this section blends history, exploration, and splendid Colorado landscapes.

16 | Big Bend AHRA Site

AHRA’s Big Bend: A Scenic Stop Along the Arkansas River

The Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area at Big Bend site is one of many developed areas along the 148-mile-long state park, which stretches from Pueblo Reservoir to near Leadville. For details on Big Bend’s amenities and other recreation sites between Salida and Buena Vista, visit AHRA Big Bend.

Big Bend offers restrooms and a parking area, making it a great access point for fishermen, boaters, and cyclists. Cyclists looking for an out-and-back ride from Salida can use Big Bend as a convenient turnaround before the section ends at US 285. Those drivers or cyclists continuing on the Stage & Rail route can turn north onto US 285, a highway with wide bikeable shoulders, and ride 1.7 miles to CR 191, where the historic gravel route picks up again. Travelers coming from the north should follow these directions in reverse.

⚠️ Important Note: The Stage & Rail route is not officially designated on US 285 or any other highway managed by CDOT (Colorado Department of Transportation). Riders and drivers must follow all CDOT regulations when using these roads.

17 | Pike Memorial

The 1806-07 Pike Expedition: A Harrowing Chapter in the Upper Arkansas Valley

The 1806-07 Pike Expedition carved out a fascinating chapter in its dramatic story as it ventured through the Upper Arkansas Valley. After an unsuccessful attempt to climb what would later be named Pikes Peak near present-day Colorado Springs, Pike split his party in two. While a smaller group turned back east, Pike led the larger contingent westward from Cañon City, determined to find the headwaters of the Red River.

By late December 1806, Pike and his men crossed Trout Creek Pass, descending into what he mistakenly believed was the Red River Valley—in reality, it was the Arkansas River Valley. The harsh winter conditions proved brutal for his poorly equipped team. Splitting his party once again, Pike and two men traveled north along the east side of the Arkansas, while the others headed south in a desperate hunt for much-needed game.

Pike's northern trek brought him near today's Hayden Valley, south of Leadville, where from west of the river he gazed upon distant towering peaks and concluded he was near the river’s source. Recognizing his small party’s lack of food, and vulnerability in subfreezing conditions, he turned south, crossed the ice-choked river several times, and eventually reunited with his men—just in time to share in an expedition-saving feast on buffalo they had shot. The party camped near Squaw Creek, just north of Big Bend, celebrating Christmas Eve and Christmas Day of 1806 resting and replenishing their strength.

After Christmas, the group followed the river southward, camping near Salida before returning after several days march to his earlier departure point at Cañon City. It was only then, three weeks after first entering the valley, that Pike realized his mistake—he had been tracing the Arkansas River’s headwaters, not the Red River’s.

18 | Historic early road (CR193)

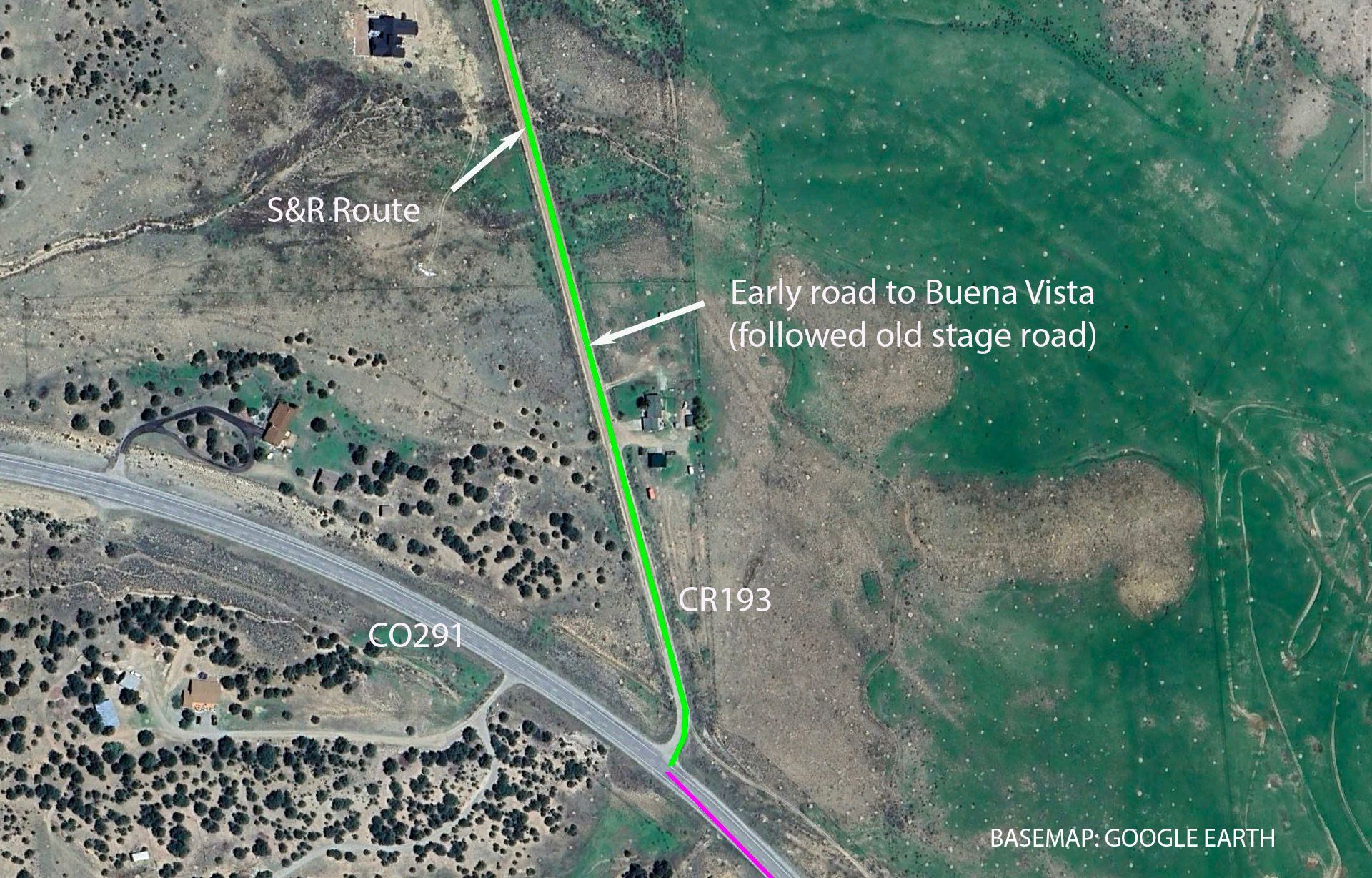

Evolution of an early route: From Busy Stage Road to Quiet County Road

Like many of America’s public roads, CR 193 has seen its share of changes over the years. What began as the 1870s stage road later evolved into an early motorable vehicle route, serving as the primary connection between Salida and Buena Vista in the early 1900s.

By the 1920s, this roadway had been upgraded to a Colorado and U.S. Highway, likely designated as US650. However, evolution didn’t stop there—when US285 was built around 1950, just a short distance to the west, it quickly became the preferred, faster, and better-maintained route, effectively replacing US 650 as the main corridor between Salida and Buena Vista.

Though no longer the primary highway, CR 193 remains a scenic and historical reminder of the Upper Arkansas Valley’s evolving transportation network.

19 | Historic early road (CR260)

CR 260: Scenic Return to a Slower Era

For both motorists and cyclists, CR 260 offers a peaceful retreat from the high-speed traffic of US 285. Winding through the valley near the base of the high-rising 14ers, this road provides a glimpse into a more relaxed era, when travel in the 1920s and 1930s moved at a gentler pace. Like CR193 (POI 18), in those early days CR260 was the primary route between Salida and Buena Vista.

Even more intriguing, CR 260 likely traces the path of the original 1870s stage road, allowing travelers to imagine slower, dustier journeys of the past—when stagecoaches and later early model automobiles navigated the same route beneath Colorado’s stunning high country.

Whether you're seeking a scenic drive or a quiet cycling route, CR 260 invites you to step back in time and experience the tranquil landscape of a previous age.

20 | Centerville Cemetery

Historic Resting Place: A Cemetery for Arkansas Valley Early Settlers

As settlers arrived in the Arkansas Valley in the early 1860s, the inevitable need for a burial ground arose. The first internment here took place in 1864, marking the beginning of a cemetery that has since become the final resting place for more than 350 individuals—though many graves remain unmarked or weathered beyond recognition.

Among those believed to be buried here are members of the extra-legal Committee of Safety, a group entangled in the infamous Lake County War of 1874-75. This turbulent period of unrest and violence, driven by disputes over land and water rights and tensions between newcomers and early ranchers, made headlines across the territory.

Today, this private cemetery holds stories of the past within its borders. Permission from the owners is required for burials but a respectful visit is likely to go unchallenged.

21 | Scenic Byway Chalk Creek Vista site

US 285 Followed the Stage & Rail: Now a Scenic Byway

Although the Stage and Rail Historic Route is not officially designated along US285, visitors likely use this highway to connect sections of the formal route. Much of today’s US285 follows the original 1870’s stage road.

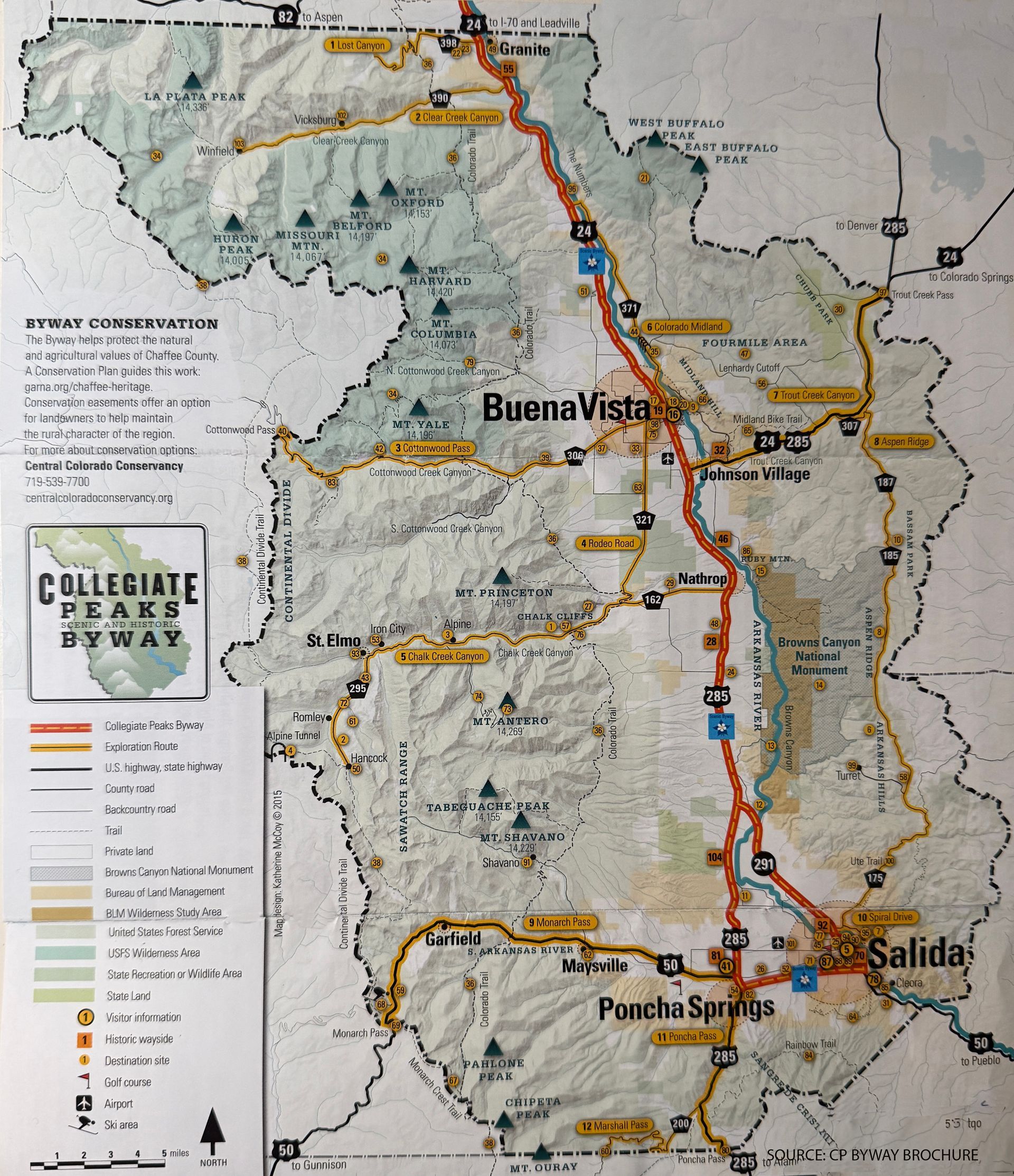

US285 is the southern backbone of the Collegiate Peaks Scenic and Historic Byway (CPSHB), a Colorado Scenic Byway (as distinct from a National Scenic Byway, managed by the Federal Highway Administration). The northern half of the CPSHB is along US24, from Buena Vista northward. Detailed information on the Byway, which stretches over 57 miles from the northern Chaffee County border to Poncha Springs and Salida, is available here. The Stage and Rail Historic Route, which both fellows and diverges from the Byway is in many ways an alternative way of experiencing it; it can slow you down, help you focus on historic sites and local stories that can be lost on a quick trip down the highway.

You can download this map at https://www.colorfulcolorado.com/collegiate-peaks-byway.

22 | View into Browns Canyon National Monument

Distant View Into a new National Monument: Browns Canyon

The Browns Canyon National Monument stretches from north of Salida to south of Buena Vista, and is visible to the east as you travel all along US285. The images below offer a distant introduction to its northernmost reaches. (For more on the Monument, see POI 24.)

Except for private agricultural properties at the foot of the mountains, virtually all the higher landscape to the east, including the Monument, is public land managed by the US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Together with lands in the high-country west of the highway, and State lands along the river, over 80% of Chaffee County is publicly owned and managed. These relatively undisturbed natural resources contribute to the ecological health of the valley by conserving intact watersheds and providing habitat for wildlife. They are also keystones of the county’s economic base in outdoor recreation, from backcountry skiing to 14er climbing, backpacking, rafting, kayaking and fishing on the Arkansas River whose flow and high quality is maintained by these healthy watersheds locally and upstream.

For more on the significance of these public lands, and remarkably successful ongoing community efforts to recognize their value and assist public land managers in providing good stewardship, see this summary of progress from the Envision Chaffee County program.

23 | Gas Creek Schoolhouse

The Gas Creek School: One of the Route’s Historic Hints into the Past

The Gas Creek School is only one of several school houses and other historic structures on the National Register along the S&R Historic Route. Most are on private land and not open to the public, but still can be appreciated from the route.

There is a fascinating interactive map that identifies and briefly describes other National Register Properties in Chaffee County, including Granite’s Commercial Hotel and Pine Hall.

Responsibility for identifying and monitoring important historic resources like the Gas Creek School has been assigned to the Chaffee County Heritage Advisory Board. This is part of the Board’s oversight of historic and natural resources throughout the county-wide Chaffee County Heritage Area, declared in 2004. The Board’s early work included successful nomination and planning of the Collegiate Peaks Scenic and Historic Byway in 2006. The Greater Arkansas River Nature Association GARNA serves as the Board’s executive and financial arm.

The Stage and Rail historic route is in many ways an alternative way of experiencing the Collegiate Peaks Scenic Byway in Chaffee County and its sister byway Top of the Rockies National Scenic Byway in Lake County. By guiding visitors to slower, quieter offshoots of the two byways there are additional opportunities to explore and absorb hidden stories of historical places and events.

24 | Access to Browns Canyon Nat Monument

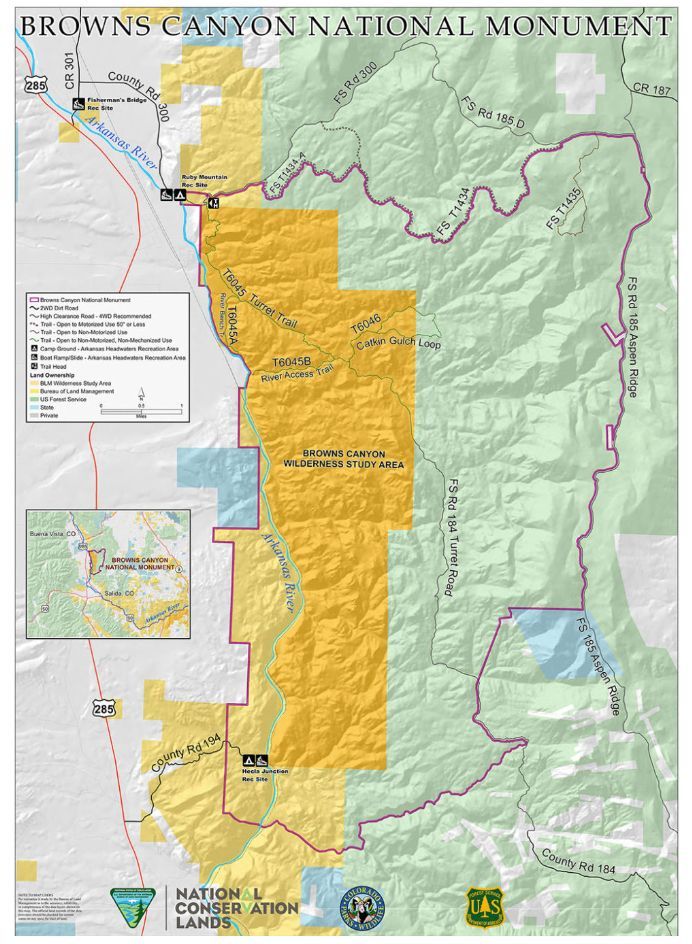

A New National Treasure: Browns Canyon National Monument

Browns Canyon National Monument is one of the nation’s newest protected landscapes, officially designated on February 19, 2015, by then-President Barack Obama. Spanning 21,586 acres, this rugged expanse of BLM and U.S. Forest Service lands—supported by participation of the State of Colorado and its Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area—stands as evidence to both its natural beauty and persistent conservation efforts by citizens and lawmakers.

Though relatively small compared to other national monuments, Browns Canyon was once envisioned on a much grander scale. In 2005, Colorado representatives proposed a Congressionally mandated Browns Canyon Wilderness Area under the 1964 Wilderness Act, a plan that would have safeguarded a significantly larger area. However, recognizing the political hurdles in securing bipartisan support, local advocates and Congressional supporters eventually revised their strategy—rallying behind a national monument designation through use of the Antiquities Act. Their efforts paid off, ensuring permanent protection for this basically wild and undisturbed landscape, although some proponents of a more restrictive legislative Wilderness were disappointed.

Today, Browns Canyon provides a near-wilderness experience, managed under a plan developed through extensive public input and NEPA compliance. Formal trails are deliberately sparse, and mechanized equipment and vehicles are restricted to a single pre-existing route. Most visitors experience its weathered beauty by rafting or kayaking the Arkansas River, navigating challenging whitewater rapids while catching fleeting glimpses into the remote interior. For those who seek a more direct foot-powered encounter, the Ruby Mountain Trailhead at the north end offers a few miles of signed hiking trails. But since most of the Monument is without developed trails, would-be explorers should be well-prepared and experienced to venture into the heart of the Monument—where steep knobby ridges, remote gulches, scarce water, route-finding puzzles, and sweeping vistas await.

The Friends of Browns Canyon, a dedicated nonprofit volunteer group, was instrumental in securing the Monument’s designation and continues to play a vital role in its stewardship. Their ongoing collaboration with the BLM and USFS helps ensure this remarkable landscape remains wild, protected, and open to foot-powered discovery for generations to come.

25 | Historic Dairy Farm

A Prison Runs a Dairy Farm (For Many Years)

In 1889, the Colorado State Legislature authorized the construction of the Colorado State Reformatory, located just west of what is now Johnson Village. By 1896, the facility had begun housing inmates, and in about 1906 it expanded its operations in a unique way—by establishing a dairy farm.

In a program to rehabilitate young offenders, the reformatory acquired 480 acres of land along CR 301, the route of the old stage road, and put trusted inmates to work on the farm. From 1906 to 2000, this dairy operation thrived, earning a reputation for hosting one of the finest Holstein herds in Colorado.

Though the land remains under the jurisdiction of the Correctional Facility, it is no longer used for inmate programs and serves solely as agricultural property. However, travelers passing through are prohibited from stopping, and signs warn against picking up hitchhikers. The historic building is not open to the public.

For a deeper dive into this fascinating piece of Chaffee County history, check out the Chaffee County, Colorado, Historic Resources Survey, 2011-13, page 57. In addition to this description, the Survey provides a wide-ranging and detailed account of the area’s historical sites and key agricultural industries, from haying and cattle ranching to dairy farming and lettuce production. It’s a great armchair resource for all of Chaffee County’s fascinating and varied history.

The historic building that served as the dairy farm headquarters was the 1886-built home of the area’s original owner Philo M. Weston. This was the man for whom the 1870’s route over Weston Pass in Lake County was named. That toll road was yet another of the alternative routes for stagecoaches and freight traffic to reach Leadville from Denver.

26 | Historic stage station barn

Another Stage Station, Approaching Buena Vista

A glance at the aerial map reveals the evolution of travel routes leading into Buena Vista—from the rugged stagecoach era to the dawn of automobile highways.

In the 1870s, the old stage road from Salida northward generally followed the west side of the Arkansas River, but it made an eastward crossing at Fisherman’s Bridge before pressing on north. However, as it neared Buena Vista, towering cliffs along the east bank made further travel impossible, forcing the road builders to construct yet another river crossing at this very location.

Here stood a stage station, possibly predating even Buena Vista’s own. This outpost provided overnight accommodations, a barn, and stables, where weary horses were swapped out for fresh teams before travelers continued their arduous journey to Leadville. To get a sense of what those wild rides were like—including the hardships and adventure of stagecoach travel—check out Legends of America for a captivating dive into Old West stage lines.

By the early 1900s, a new kind of road arrived at this same spot. A bridge just upstream carried the first motorized vehicles into Buena Vista from the east—a precursor to what would later become US 285 and US 24, descending from Trout Creek Pass. This wasn’t just any road; it was part of a grand promotional vision.

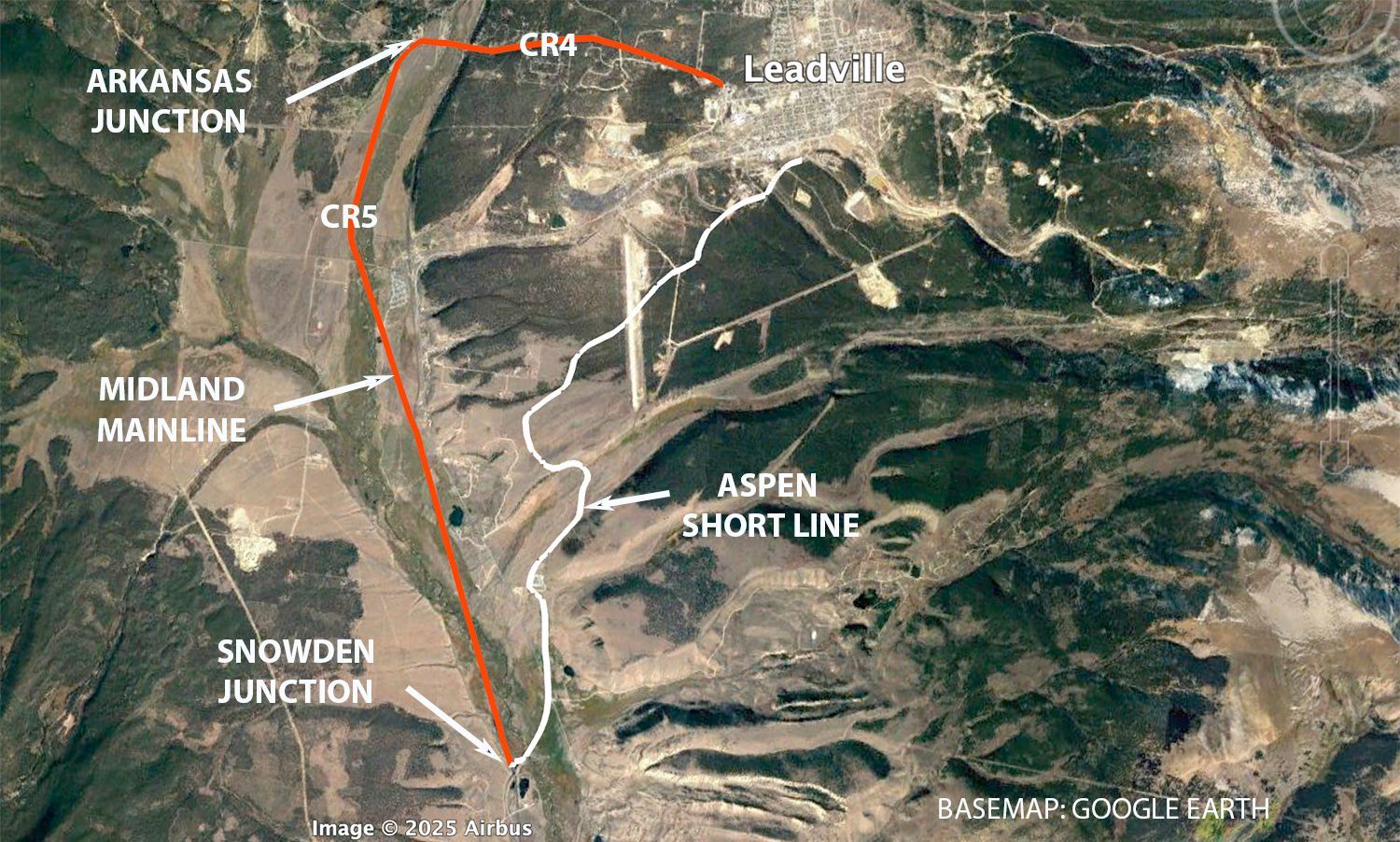

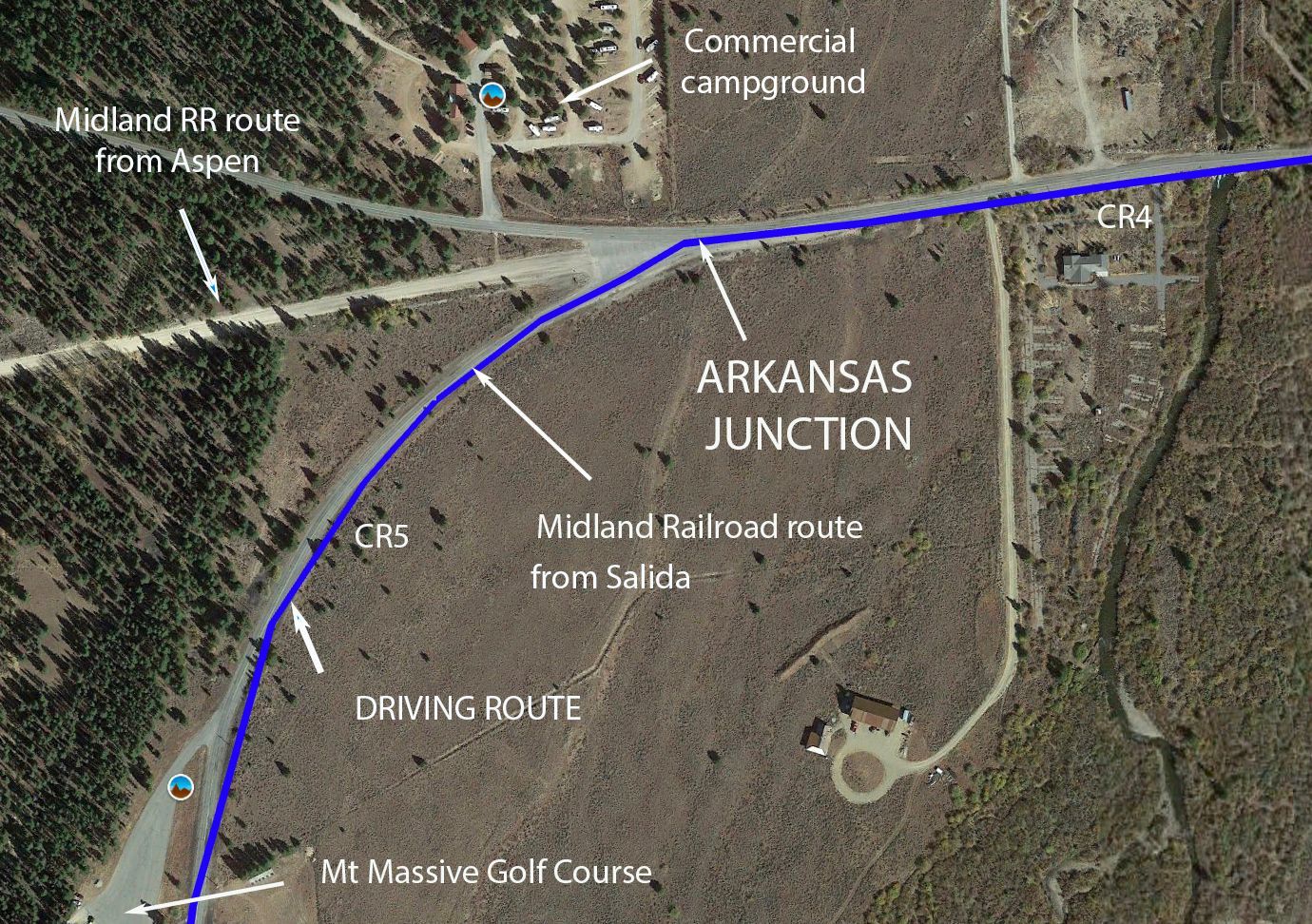

In 1914, as automobiles surged onto the American scene, a cross-country route called the Pikes Peak Ocean to Ocean Highway (PPOO) was proposed. By 1924, it stretched from New York City to Los Angeles, offering an alternative to the more famous Lincoln Highway which traversed the country to the north. Following some of the old stage road routes, early motor highways like the PPOO shaped today’s Chaffee and Lake County roads—a direct link between pioneering stagecoach paths and modern roadways.

PPOO brochures from the 1920s paint a vivid picture of early road-trip tourism in the Upper Arkansas Valley. They lured travelers with free campgrounds, scenic highlights, and local attractions—much like today’s Buena Vista and Leadville tourism websites.

27 | Buena Vista Heritage Museum

A Town’s History Preserved

The Buena Vista Heritage Museum offers a fascinating glimpse into the town’s evolution—from its humble beginnings in the 1860s to its late-century rise as a bustling hub for ranching, mining, and transportation.

In those early days, settlers were drawn to BV’s fertile lands, ideal for agriculture, and its prime location to serve the booming ranching and mining industries. By the late 1860s, the town thrived as a key stop for stagecoaches, with up to a dozen daily arrivals, bringing passengers and mail on their way to Granite and Leadville (then known as Oro City).

Ranchers and merchants from across the valley traveled to BV for supplies, transported by horse- and mule-drawn freight wagons over the rough stage roads and pioneer trails from Trout Creek Pass, Colorado Springs, and even Denver.

The arrival of the railroads in 1880—first the Denver, South Park & Pacific and soon after the Denver & Rio Grande—launched a new era of expansion. By 1887, the Midland Railroad further cemented BV’s role as a key regional hub. Growth continued into the early 1900s, as improved highways connected the town to Salida and the Front Range—though BV’s Main Street remained unpaved until the 1960s!

Fast forward to the past 30 years, and Buena Vista has reinvented itself yet again. Once sustained by agriculture, railroads, and industry, the valley now thrives on outdoor recreation and tourism. While fishing and rafting on the Arkansas River remain deeply popular, recent decades have seen an explosion of day hiking, camping, backpacking, mountain biking, backcountry skiing, OHV riding, and the ever-growing attraction of 14er climbing.

A Heist That Made History

One of BV’s most infamous stories involves the very building that now houses the Museum—the Chaffee County Courthouse.

When Chaffee County was officially created out of Lake County in 1879, the then booming mining town of Granite claimed to be its first county seat. After a vote, more diversified and centrally located Buena Vista was selected—but Granite refused to accept the decision.

In November 1880, a determined group of BV citizens took matters into their own hands. Commandeering a train and railcar, they stormed Granite under cover of night, held off the local sheriff, and raided their rustic courthouse. They seized county records, furniture, and anything else of value, loading it onto the train and hauling it all back to Buena Vista!

With the questionably obtained goods now in BV, the town had no choice but to hastily construct a courthouse, completing it by 1882.

However, BV’s reign was not permanent—by 1934, after another vote, the county seat moved again, this time to the larger and more-rapidly expanding town of Salida. For the next 30 years, the former courthouse found new purpose as a K-12 schoolhouse, serving BV’s growing population. Many of the town’s current older residents passed through those schoolhouse times.

When the school finally shut its doors in 1972, there was a real threat the courthouse would be torn down. However, with leadership by a few local citizens with a passion for preserving the past, the non-profit institution Buena Vista Heritage was born. Its initial focus was preservation of the courthouse, but also ensuring its long-term survival by establishing a museum and active educational programs and publicly available archives. That the Museum—and the Courthouse—are still a beloved community resource over 50 years on is a testament to the vision of those early supporters, and the dedication of a new generation of equally-committed Heritage allies.

28 | BV Depot Transportation Museum

A Continuing Tribute to Buena Vista’s Railroad Legacy

The railroads shaped Buena Vista, fueling its growth, commerce, and connection to the wider world. Recognizing their pivotal role in the town’s history, local citizens and Buena Vista Heritage united to save and restore a piece of that past—the original Denver, South Park & Pacific Depot.

Now reborn as a transportation museum, the depot brings the 1890s railroad era back to life. Inside its carefully restored interior, you’ll find a historic waiting room, the station manager’s office, and even the manager’s residence—each fitted with exhibits that immerse you in the Buena Vista’s heyday of rail travel.

The museum also traces the arrival of the automobile and the impact of the Pikes Peak Ocean to Ocean Highway which ushered in a new era of motorized tourism.

Open at limited times in summer, the Depot makes a great short pause as you pass through Buena Vista, providing a vibrant visual sense of the importance of the rail lines and early travel through the Upper Arkansas Valley.

29 | Downtown Buena Vista

Buena Vista: A Town Built on Ranching, Rails, and Resilience

Buena Vista’s early history sets it apart from neighboring towns like Salida and Leadville. While Salida sprang to life as a railroad hub and Leadville boomed with mining, Buena Vista’s first settlers arrived in 1864, drawn not by industry, but by the promise of fertile land for ranching and agriculture.

Originally called Mahonville, the town remained a quiet ranching community for over a decade. Stagecoaches began arriving in the mid 1870s, not only transporting mail and passengers to Leadville, but also connecting the town to the wider world of Colorado and beyond. But big changes started happening around 1880, when it was renamed Buena Vista and began preparing for a new future as a junction of three ambitious and competitive railroad companies. The Denver, South Park & Pacific and the Denver & Rio Grande railroads arrived in 1880, followed by the Midland Railway in 1887. As the iron tracks pushed toward Leadville and beyond, Buena Vista became a key supplier of hay, vegetables, and lumber—essential goods for the exploding mining towns of the Upper Arkansas Valley. For a thumbnail sketch of this period of stage routes, freight roads and railroad dominance, see the Chaffee County Times article by renowned local historian Suzy Kelly.

The late 19th century was a wild, rowdy time for Buena Vista, filled with booming business, rough saloons, and a frontier spirit. There are a dozen or more historic sites in and around Buena Vista on the national register which date from those years.

For a fascinating insight into this era, including rare early photos, check out this impressive summary.

As the mining boom faded and the early railroads fell silent, Buena Vista gradually evolved into a more typical small rural Colorado mountain valley town—one that balanced its agricultural heritage with new opportunities.

By the mid 1920s, both the Denver, South Park & Pacific and the Midland Railway had ceased operations. The Denver & Rio Grande held on much longer, providing profitable service until it was eventually absorbed by the Union Pacific Railroad, which ran its last train through the valley in 1999.

With the decline of mining and railroads, Buena Vista turned more to its agricultural roots. The town remained a center for hay production and cattle ranching, but also saw shifts in farming—including a thriving dairy industry and a period when Buena Vista became famous for lettuce production. During summer months, locally harvested heads of lettuce were shipped nationwide by rail, kept fresh and cool by massive blocks of ice harvested from the town’s iconic Iceberg Lake each winter.

As the 20th century ended, Buena Vista—like nearby Salida—began to embrace a new identity: as a destination for outdoor recreation. Today, the town’s economy thrives on fishing, rafting, and kayaking on the Arkansas River, as well as hosting a raid expansion of hiking, cycling, backpacking, peak-climbing, and off-highway vehicle (OHV) adventures on the widespread public lands surrounding Buena Vista. Equipment service, sales and rental stores do big business, and restaurants, short term rentals, Airbnb opportunities and retail shops are currently enjoying success. New housing projects are booming.

Particularly in the past 30 years, an important influence on Buena Vista’s economy as well as Chaffee County’s demographics has been the substantial influx of retirees who have built year-round homes in subdivisions outside city limits; another change has come with the advent of the Internet and its facilitation of remote work opportunities, allowing younger professionals from elsewhere to seek out the benefits of raising families outside the urban rush, and encouraging young people raised in Buena Vista to return after training outside the valley.

From railroads and ranching to rafting and recreation, Buena Vista has continually reoriented itself—while staying true to its deep roots in Colorado’s mountain heritage.

30 | Historic Wildhorse/Midland RR yard

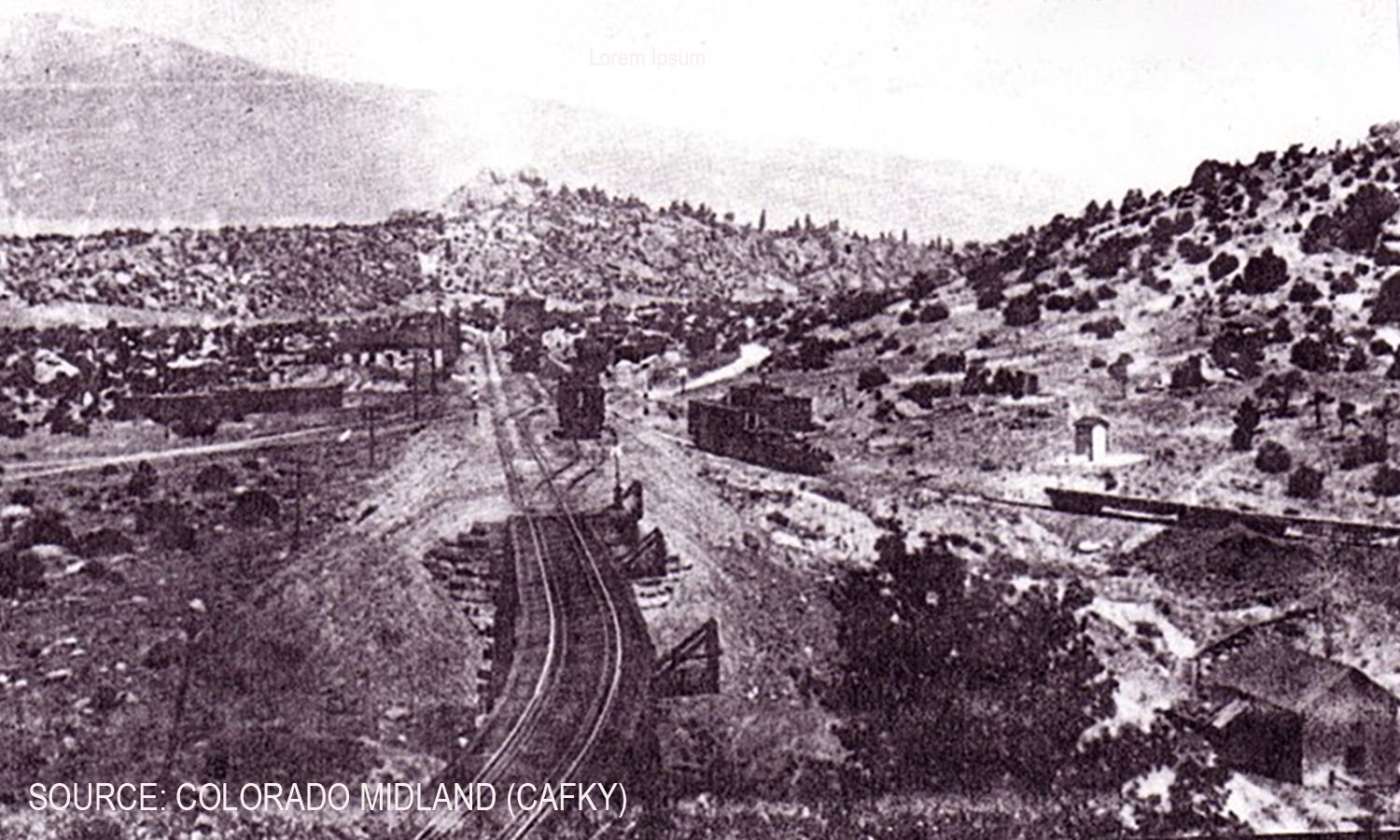

The Midland’s Depot and Yards in Buena Vista

Unlike the other rail lines that made their way directly through town, Midland’s engineers took a different approach. To maintain elevation on the climb to Leadville, they deliberately kept the tracks above Buena Vista, placing its main depot high on the hillside east of the river, where CR 304 runs today. That required transfers of passengers and baggage down the “hack road” into town.

For its maintenance yard, sidings, and water tank—vital for recharging steam locomotives—on arriving in 1887 the Midland chose a broader expanse just north of town. This area, known as Wild Horse became a busy railroad hub with its own depot, repair buildings, employee housing, and even a school. It remained active until 1921, when the last Midland freight train rolled through. Later, the steel rails and trestles were dismantled, repurposed as scrap for the war effort during World War II.

The journey from the Midland depot above Buena Vista to Wild Horse was short, but it presented significant engineering challenges. The railroad had to span several deep gulches, including the dramatic Hop Gulch and another gulch just south of Wild Horse. The Hop Gulch trestle, one of the Midland’s most daring constructions, was an astonishingly high and spindly-appearing structure, among the tallest—and most fragile-looking—of the dozen or more trestles that once stood between Trout Creek Pass and Leadville.

While some Midland trestles—like those at Hop Gulch and Clear Creek—were built with steel, others, such as those crossing shallower Shields and McGee gulches in the Fourmile area, were entirely wooden. Wooden trestles were highly vulnerable, whether to wildfires or accidents like a near-disastrous fire at the McGee Bridge in the 1890s, when hot cinders from passage of a coal-burning locomotive threatened to ignite the entire structure. The next-arriving locomotive’s engineer was able to stop his train when just the engine had just begun crossing, partially collapsing only the smoldering end.

Though Midland’s tracks are long gone, echoes of its railroading legacy remain in the form of impressive cuts and fills, missing trestles, and long gentle grades now used as popular hiking and biking trails—reminders of a time when steel, steam, and ingenuity carved permanent pathways through the rugged Upper Arkansas Valley’s hills.

31 | Midland Railroad Tunnels

The Midland Railroad Tunnels: A Relic Recorded in Photographs

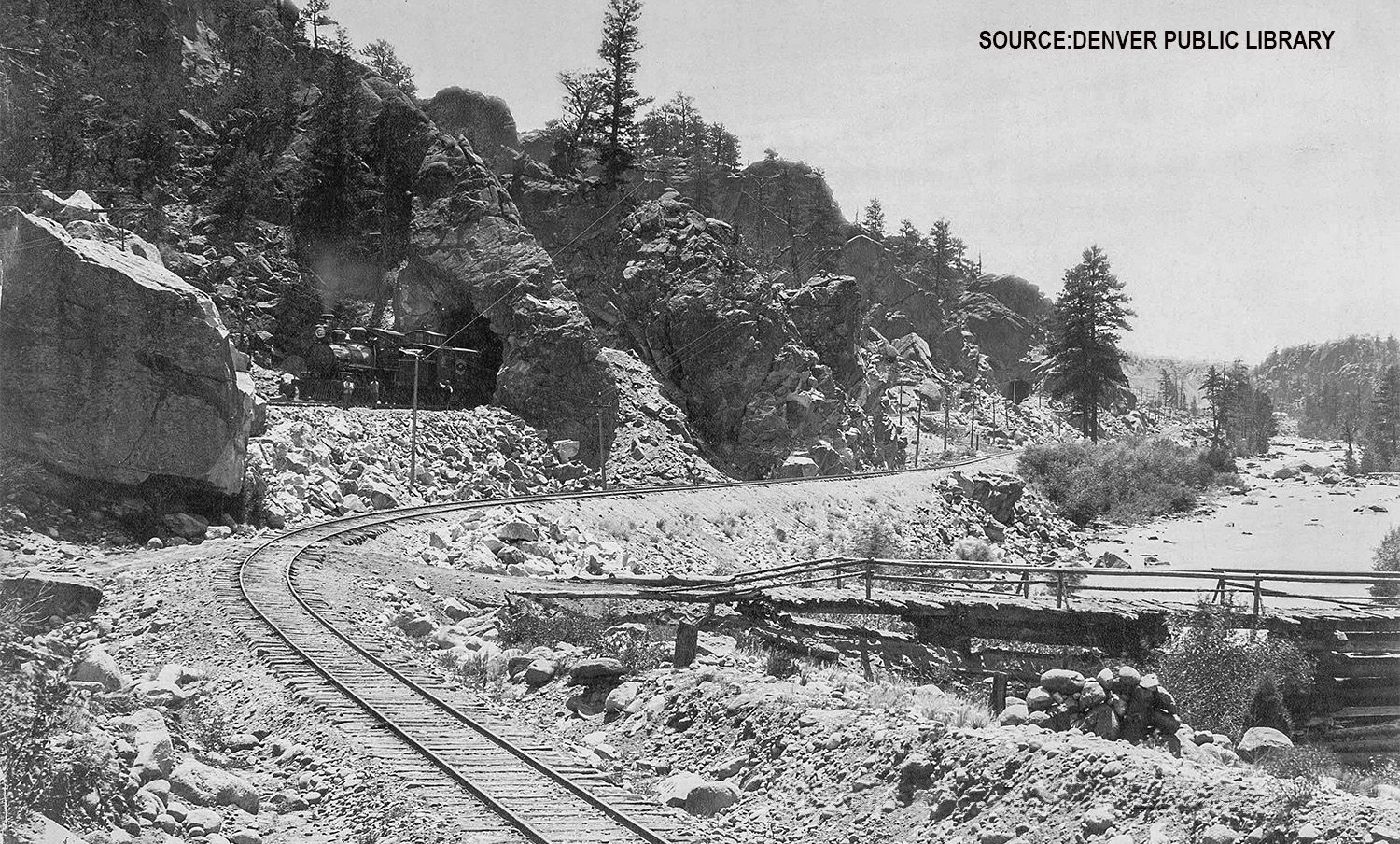

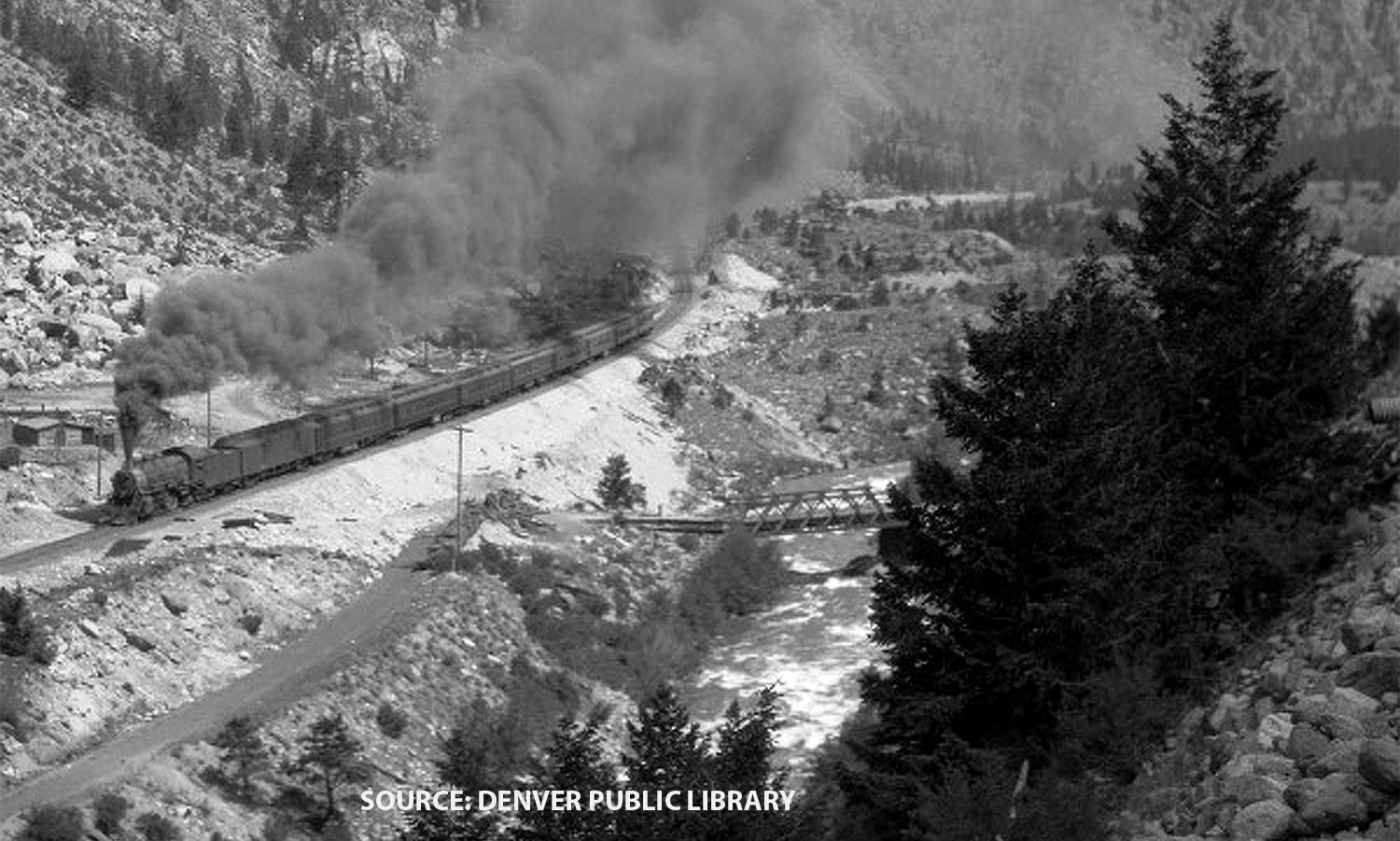

By the time the standard-gauge Midland Railroad reached north of Buena Vista in 1887, the Denver & Rio Grande had already laid claim to the narrow space along the river, having built its narrow-gauge tracks there in 1880. With little choice, Midland engineers had to carve their own path—literally—by blasting through the cliffs, creating the four iconic tunnels that remain a historical landmark today.

Luckily for us, this chapter of Midland’s history was documented on film. Shortly after completing the tunnels, the railroad commissioned the renowned Denver-based photographer William Henry Jackson to ride and photograph the entire Midland route. His images, an invaluable visual archive of early Colorado railroading, provide a glimpse into the past that would later inform and inspire future photographers and historians.

More than a century later, the equally celebrated Colorado photographer John Fielder took on a monumental project. In his two volumes, Colorado 1870-2000 and Colorado 1870-2000 II, Fielder painstakingly rephotographed Jackson’s original images, juxtaposing them to showcase the remarkable changes—and enduring similarities—over 130 years. His work offers a powerful reflection on the passage of time in Colorado’s landscapes.

Shortly before his passing in 2023, Fielder generously donated many of his iconic images to History Colorado, making them accessible to the public. You can browse and even select images for printing, ensuring that these photographic heirlooms remain alive for future generations.

For a lyrical account of running through the tunnels, check out this inspiring personal narrative.

32 | Stage road crossed river

Crossing the Arkansas: The Stage Road Switches Sides (Again)

For the early stage road engineers, building a route along the Arkansas River was no simple task. They had to prudently choose which side of the river to follow, balancing terrain challenges with the need to reach key destinations. For example, getting to Buena Vista required crossing from east to west just south of town (see POI 26).

Coming north out of Buena Vista, the stage road originally ran along the west bank. However, as the canyon narrowed, the engineers realized the east bank provided an easier road-building pathway, at least for the few miles leading to today’s Railroad Bridge campground (POI 34).

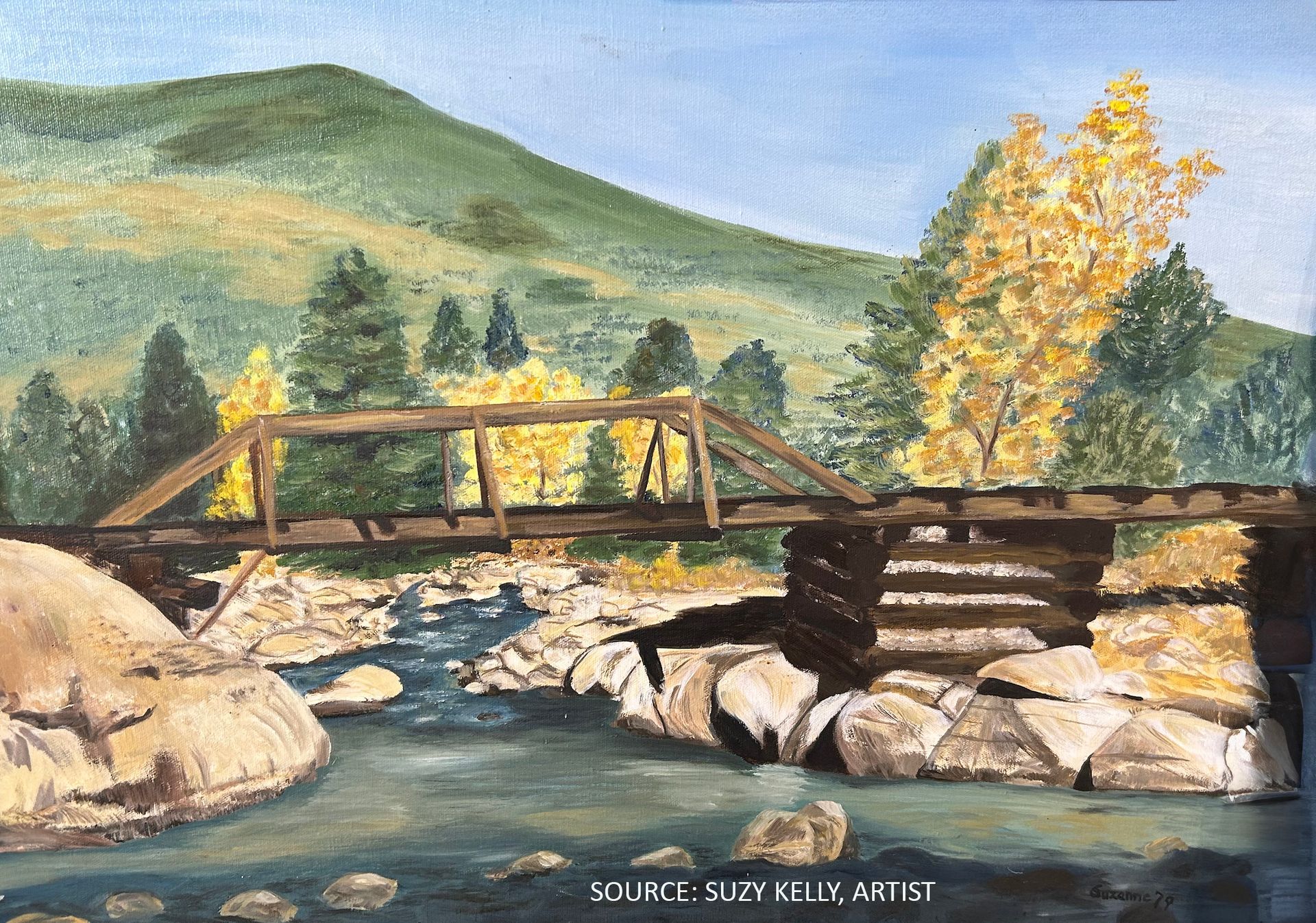

The remarkable 1887 photograph by William Henry Jackson offers proof of this crossing, and further investigation led to the discovery of physical remains of bridge support structures. Evidence suggests that bridge locations may have shifted over time, either due to flood damage or the decision to build in a more protected site.

The ever-diverse landscape of the Arkansas River Valley meant that early road builders had to adapt constantly as they built northward, leaving behind clues that continue to tell their story today.

33 | Elephant Rock

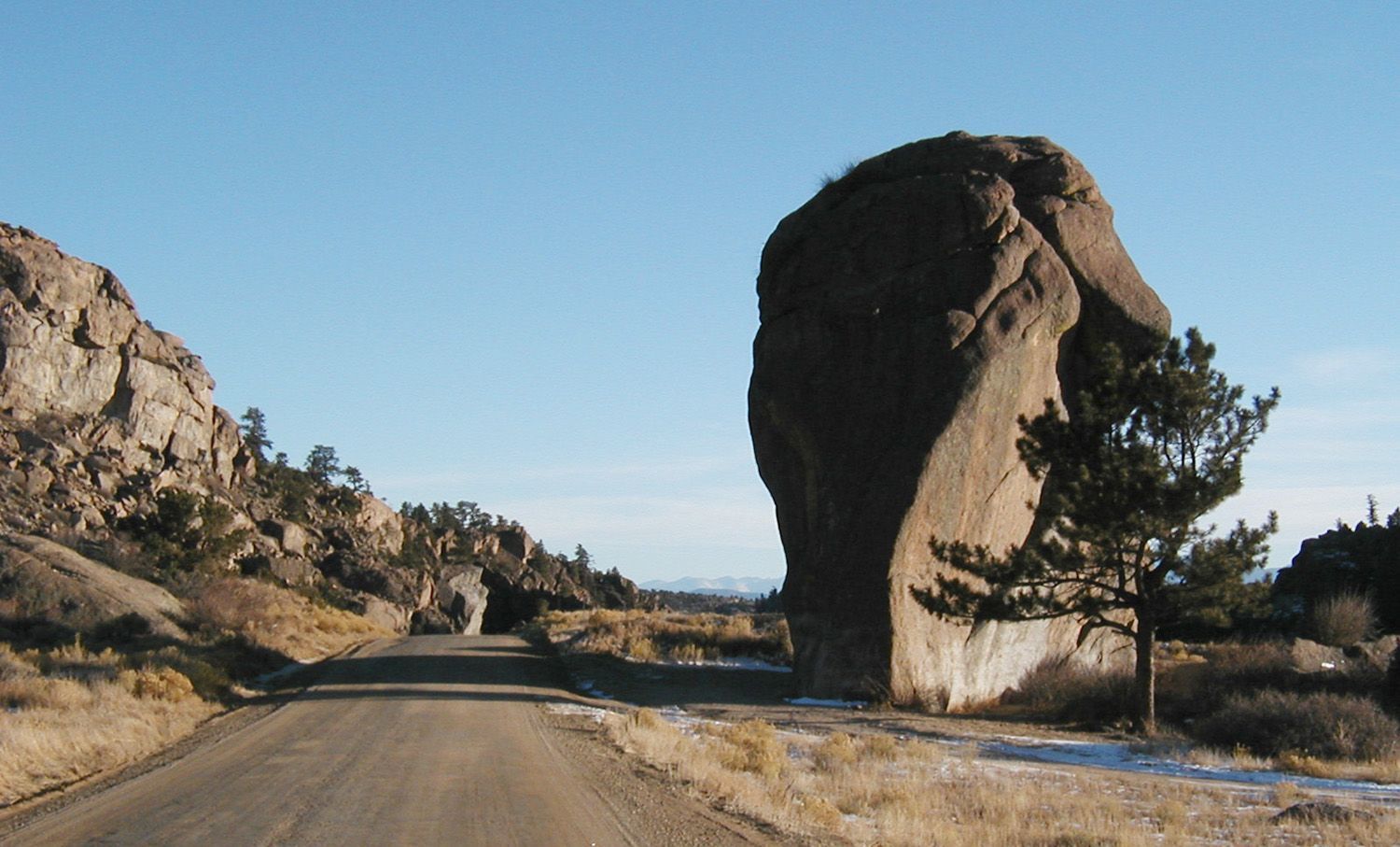

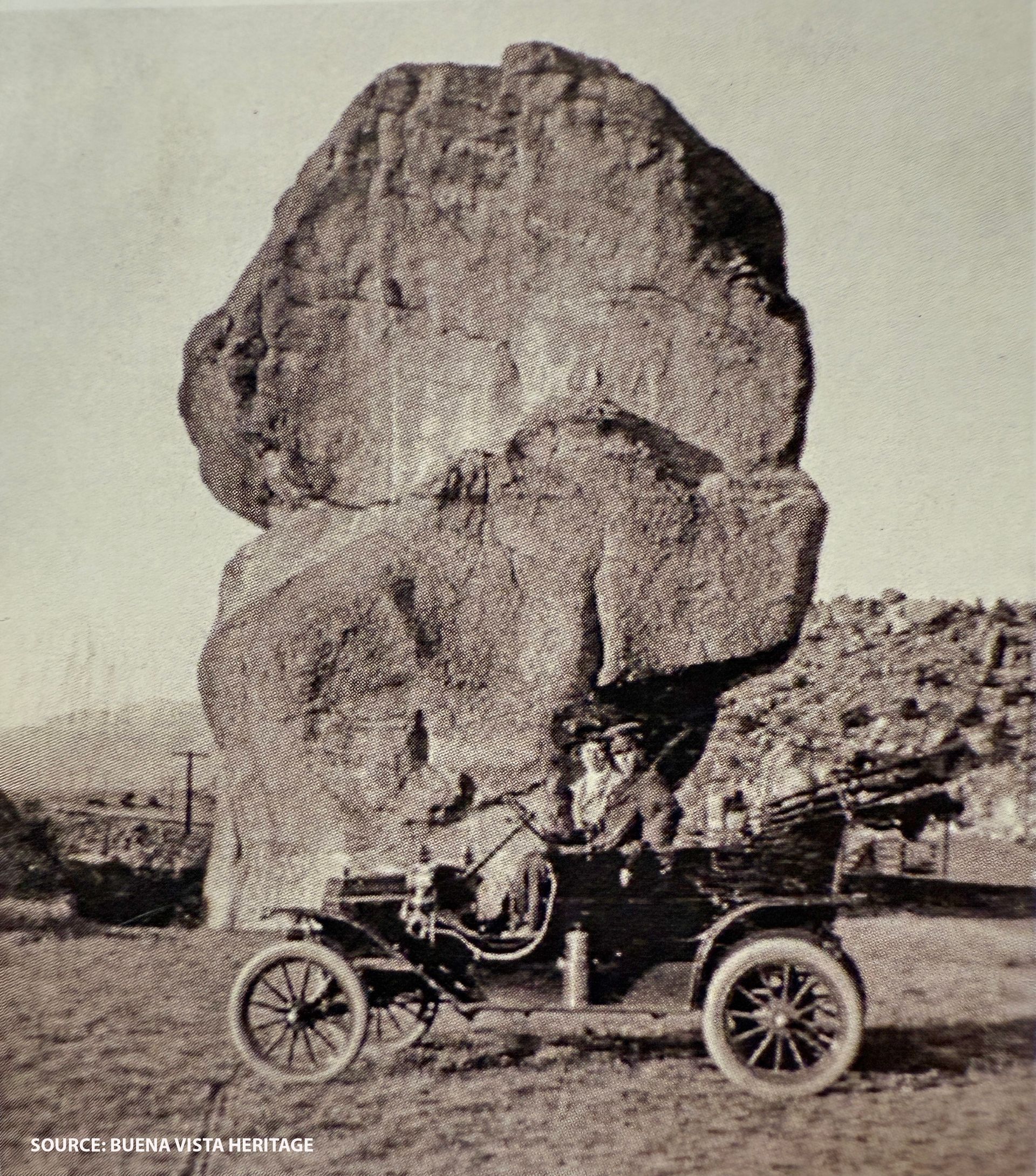

Elephant Rock: A Peculiarly Shaped Landmark

The unique shape of Elephant Rock has been a well-known feature of Buena Vista’s landscape since the town’s earliest days. When the Midland Railroad was in operation, its tracks passed just a few feet from the rock, making it a popular stop. Passengers often disembarked to take a stroll and pose for photographs with the impressive formation.

Today, the habit of visiting Elephant Rock continues. The Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area has established a small, first-come, first-served Elephant Rock camping area near the rock, offering a unique overnight experience only a few hundred feet from the river. For those seeking a more developed site, AHRA’s Railroad Bridge Campground, located farther north, is available by reservation, and requires a fee.

Whether you’re camping, exploring, or simply admiring this natural feature, Elephant Rock remains an admired landmark in the Upper Arkansas Valley.

34 | Stage road crossed river

AHRA Railroad Bridge Campground: A Crossroads of Stage and Rail History

The AHRA Railroad Bridge Campground sits at a historically significant location along Buena Vista’s early transportation routes.

- For millennia prior to arrival of Europeans, indigenous Native Americans likely passed this way in search of buffalo, deer and elk.

- On a frigid day in late December 1806, Zebulon Pike apparently came by en route to concluding he had discovered the source of the river from his turn-around point south of Leadville (see POI 17).

- In the 1870s, the stage road was the first constructed route to arrive, crossing the Arkansas River at the north end of the campground.

- The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad (D&RG) followed in 1880, initially as a narrow-gauge railway. In 1926, it was upgraded to standard-gauge, and today, its legacy continues as the modern but inactive Union Pacific line, visible just west of the campground where it crosses the river.

- The Midland Railroad arrived in 1887, choosing a route east of the river for most of its journey toward Leadville.

- Today, County Road 371 follows the old Midland Railroad bed, preserving its path through the valley (see POI 34A).

Visitors to the AHRA Railroad Bridge Campground are literally camping in history, surrounded by the echoes of Native Americans, stagecoaches, locomotives, and pioneers who once traveled these routes.

34A | Midland right of way on CR371

CR371: A Scenic and Historic Ride Along the Arkansas River

County Road 371 (CR371)—following the path of the old Midland Railroad—is one of Chaffee County’s most scenic unpaved roads. Stretching north from Buena Vista to the Otero Pump Station Bridge, it offers a slow-paced, picturesque drive that is popular with both cyclists and vehicle drivers.

North of Railroad Bridge Campground, CR371 closely follows the Arkansas River, offering birds-eye views of nearly continuous whitewater rapids. This section is one of the busiest boating stretches in the 148-mile Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area attracting literally hundreds of thousands of commercial and private rafters annually.

The road is well-maintained and busy year-round, especially in summer when raft company buses and trailers use it daily to access upstream put-in points. Raft company drivers are trained to watch for cyclists and oncoming vehicles, particularly in narrow sections like the Tunnels—but caution is advised for all users.

CR371 is a favorite route for mountain and gravel bikers, often used as a scenic "out-and-back" ride from downtown Buena Vista, where bikes (and E-bikes) can be rented.

35 | Midland RR stone retaining wall south

CR371: Railroads, Stagecoaches, and a River Reborn

This stretch of County Road 317 is more than just a scenic drive—it’s a living history book filled with stories of ambition, resilience, and transformation.

One of the most visible remnants of the past is the series of impressive retaining walls built by Midland Railroad engineers. They weren’t just constructing a railway; they were battling the unpredictable onslaughts of monsoon season storms, which could send tons of rubble crashing down onto the tracks. The evidence of their work remains today, testament to the challenges of taming this steep landscape.

Even before the railroad, another route made its way through these hills—the Lenhardy Cutoff, an 1872 toll road designed as a stage and freight shortcut from the east across Trout Creek Pass. Rather than detouring through Buena Vista, travelers and goods could take this more direct path to an area named Riverside and the ranch of George Leonhardy, a key supplier of hay and vegetables to the booming mining town of Leadville. His west-bank farm’s location along the Arkansas River gave him access to the Cañon City to Leadville stage route, allowing him to move goods northward with greater efficiency.

Yet perhaps the most dramatic story of this area is not one of toll roads or railways, but of the health of the Arkansas River itself. Decades ago, this waterway was heavily polluted, its fish population stunted and dwindling under the weight of toxic runoff from the California Gulch/Leadville mining districts far upstream. The EPA’s multiyear California Gulch/Leadville Superfund cleanup changed everything—filtration systems now remove heavy metals from abandoned mines, and contaminated soils have been treated and covered. The results? A once-struggling fishery rebounded so spectacularly that today, 102 miles of the Upper Arkansas—including this very section—are designated as a Gold Medal Fishery, the highest quality ranking in Colorado.

From the labor of railroad builders to the ingenuity of early settlers and the environmental victories of modern times, this humble road holds stories of struggle and success, waiting to be discovered by those who pass through.

36 | Midland RR stone retaining wall north

Exploring More on the Old Midland Railroad Route

The formal S&R historic route turns west across the Otero Pump Station Bridge on CR371; for extra out-and-back exposure to a beautiful, secluded stretch of the river and a less-visited narrow mile of the Midland Railroad, drivers and cyclists can continue along the old RR line until it reaches a dead end at private property.

Keep an eye out for the impressive 140-year-old retaining wall, built entirely from rounded river stones—a testament to the craftsmanship and local materials use of the railroad builders who once tamed this difficult terrain. Looking across the river to the west bank, you’ll find an abandoned headgate, a relic of an early 1900s canal system that once carried irrigation water to fertile croplands stretching all the way to the RR Bridge Campground.

For those seeking a quiet overnight camping stay, the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area (AHRA) offers simple designated campsites just steps away from prime fishing spots—a good place to reflect on the history and natural beauty of this uncrowded section of the old Midland and the river.

37 | Otero Pump Station Bridge

Otero Pump Station Bridge: Intro to the Homestake Water Project

Leading CR371 across the Arkansas River, the Otero Pump Station Bridge derives its local name from a critical powerful pump station located just up the hill to the east, accessible only by a private road. This station plays a vital role in the Homestake Water Project, a three decades old joint effort between Colorado Springs and Aurora to transfer highly-valued water from Colorado’s Western Slope to their growing communities along the Front Range. Using an intricate system of tunnels beneath the Continental Divide, and temporary holding lakes such as Turquoise, Twin Lakes, and Clear Creek reservoir, water is funneled into the Arkansas River Valley, then pumped over Trout Creek Pass into South Park before making its way to its final destinations. Today, nearly half the water supply for these two cities depends on this ambitious engineering feat.

You can continue northward along US 24 to explore additional sections of this historic route. For a brief but rewarding detour along the old Midland Railroad, head one more mile north before crossing the bridge (see POI 36). There, you’ll find more remnants of the Midland’s past before encountering a private property gate, marking the point where you’ll need to turn back.

As you cross the bridge to CR371’s junction with US 24, you’ll reach the end of this section of the Stage & Rail Route—but the journey doesn’t have to stop here: there are additional sections farther north.

Be aware that although the Stage & Rail Route follows historic pathways, it is not officially designated on US 24 or any other CDOT-managed highway. Travelers must adhere to all CDOT regulations while navigating these roads.

38 | Midland RR Historic bridge abutments

A Bridge Through Time: The Midland Crossing

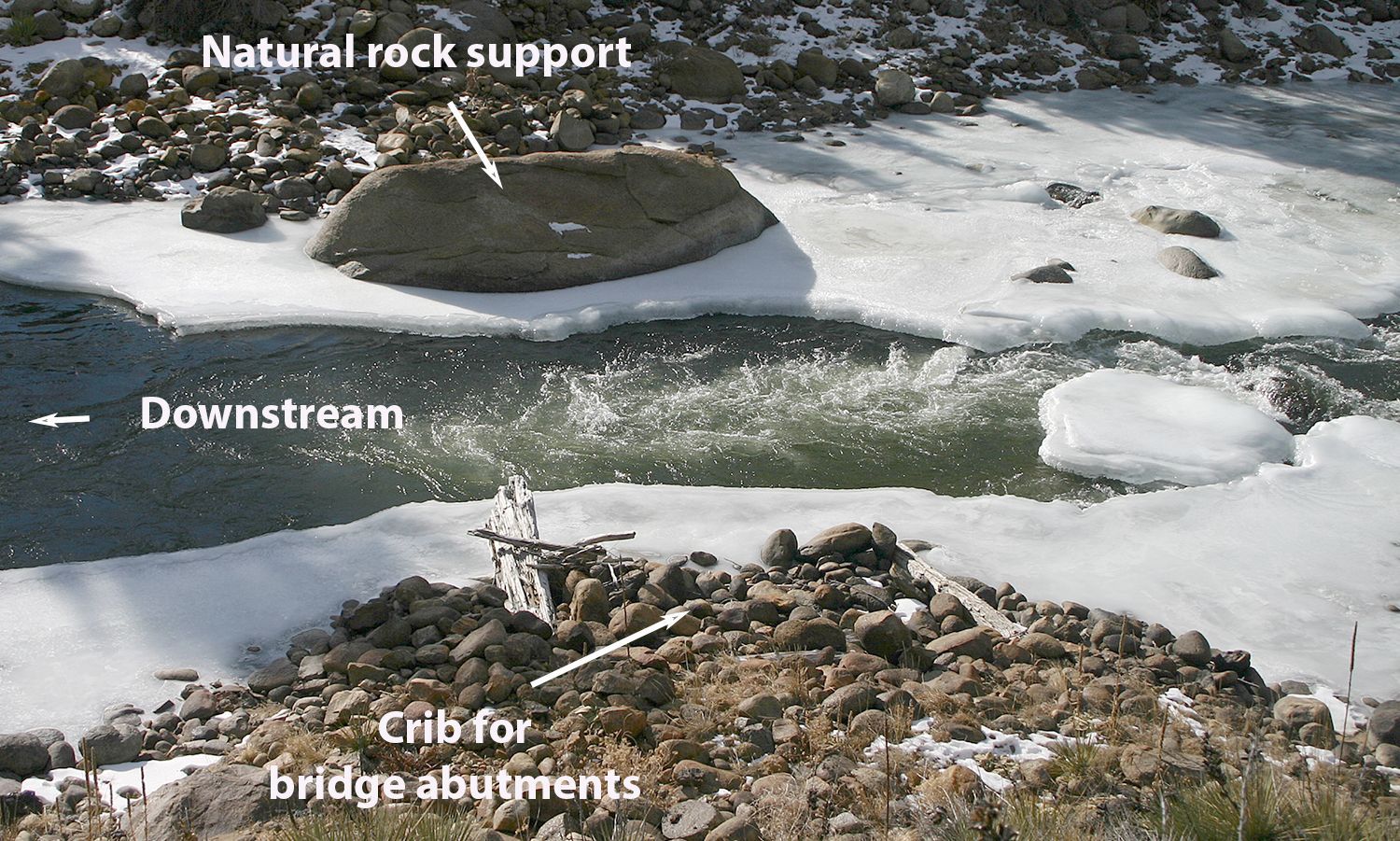

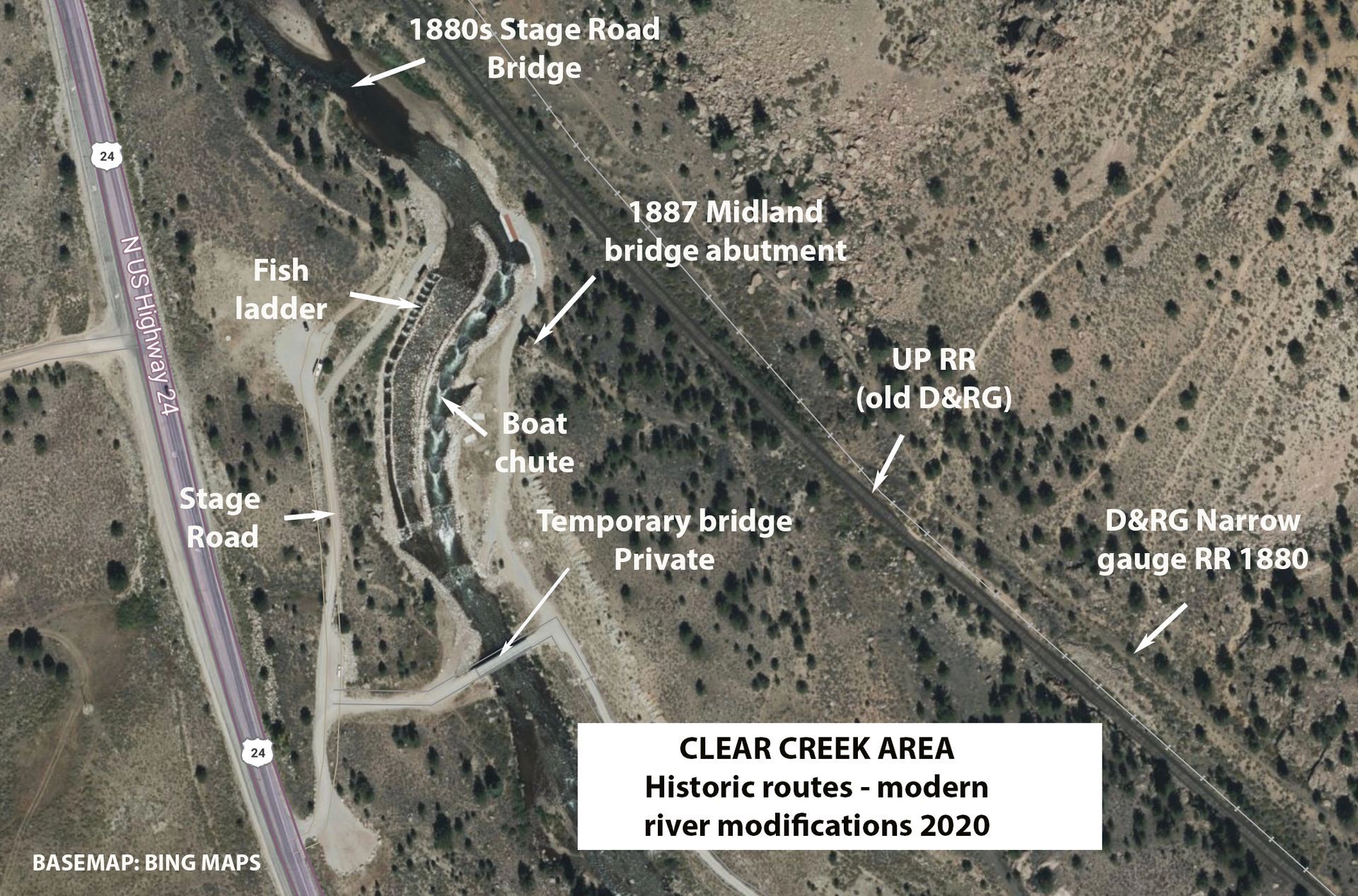

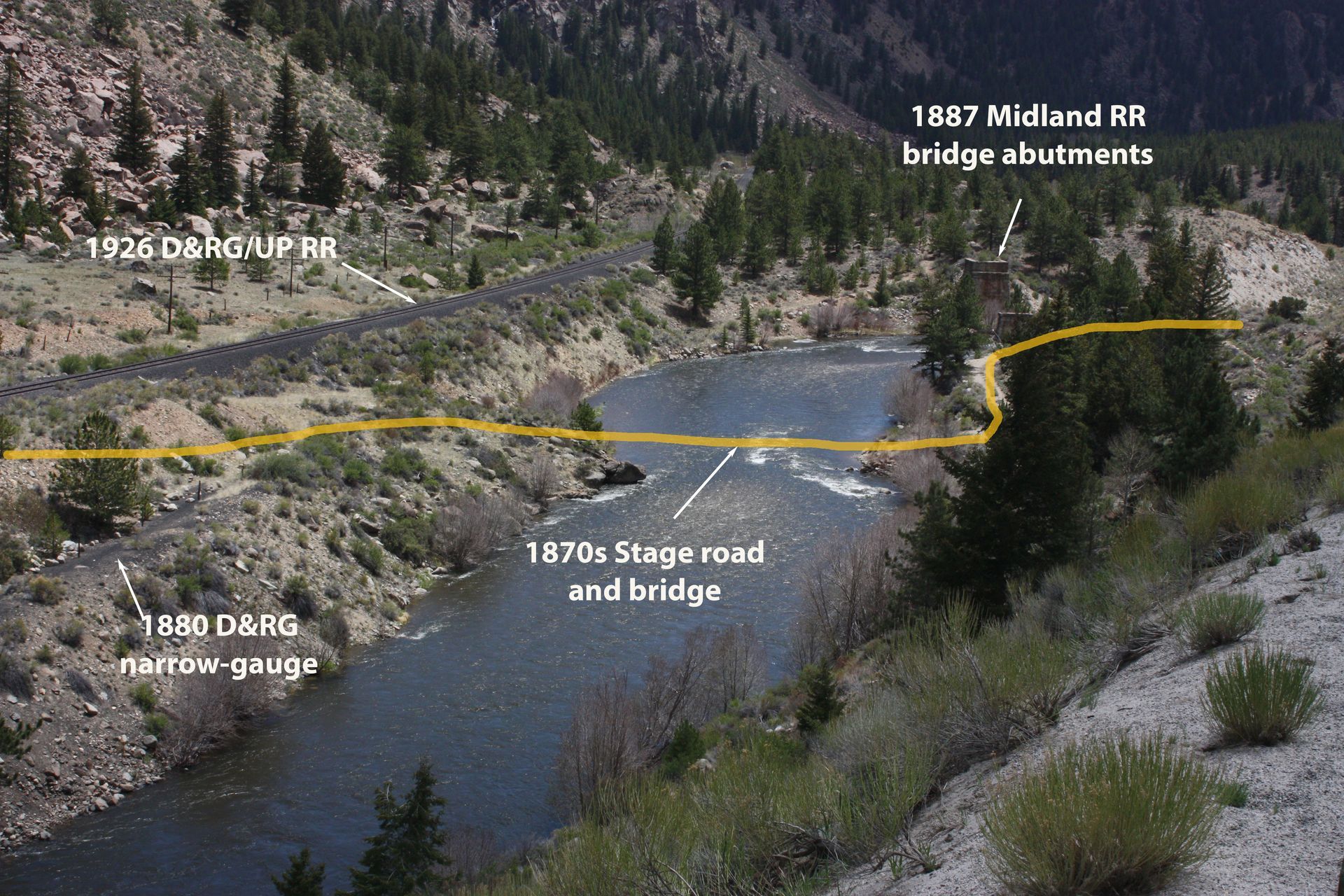

This historic bridge crossing of the Midland Railroad has a layered past. Around 1870, the original stage road crossed the Arkansas River just upstream from where, in 1887, Midland Railroad engineers constructed their own impressive span. This rail bridge was supported by locally quarried sandstone abutments, meticulously cut and assembled with precision. Since the stage road predated the railroad, the former ended up passing beneath the new bridge, hugging the northernmost abutment.

By the time the Midland Railroad arrived in 1887, the once-bustling stage route had already seen a significant decline. The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad (D&RG) had been ferrying passengers and mail to Leadville since 1880, offering a far more comfortable and efficient alternative to the grueling stagecoach journey. The Midland’s arrival only reinforced this trend, making stage travel increasingly obsolete. Though official records are scarce, it appears that the stage road persisted for a couple more decades, transitioning from a stagecoach route into a freight wagon road before fading into history.

Modern Upgrade: A Boat Chute and Fish Ladder

Fast-forward to the 1990s, when the Homestake Water Delivery Project reshaped this section of the Arkansas River. Originally, project engineers diverted water directly from the river via a low-head dam and intake system, channeling it to the Otero Pump Station for transport over Trout Creek Pass to the Front Range (see POI 37). However, with the later construction of a pipeline from Clear Creek Reservoir, the need to collect water directly from the river here was eliminated.

Over the years, the abandoned dam deteriorated, creating a hazard for boaters who were forced to portage around it. Meanwhile, it also impeded upstream fish migration. Recognizing the need for both safety improvements and ecological restoration, water managers collaborated with the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area on a multi-purpose, multi-million-dollar rehabilitation project. Their solution? A refurbished intake system, ensuring a backup water intake source if needed, alongside a new dam, a safe boat chute, and a fish ladder—enhancing both recreational access and fishery health for future generations.

39 | Stage road crossed river

A Crossroads of Early Transportation: Clear Creek and the Arkansas River

The confluence of Clear Creek and the Arkansas River was once a busy hub in the valley’s early transportation history. Engineers planning stagecoach routes and rail lines faced a common challenge—the narrowing canyon topography north of Clear Creek. Yet, each mode of transport tackled the problem in a unique way.

- The Stage Road (First to Arrive): Early stage road builders chose to cross from the west to the east bank at this point, likely anticipating difficulties ahead if they remained on the west side as the canyon tightened.

- The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad: Opting for a different approach, D&RG engineers kept their narrow-gauge track on the east bank. With a smaller footprint and the ability to navigate tighter curves, they found the east side more suitable for their route.

- The Colorado Midland Railroad (A Later Arrival): The Midland Railroad, arriving last with its wider standard-gauge tracks, made a strategic river crossing—shifting from east to west bank. This decision was likely based on the need for broader curves and gentler gradients, which the west side better accommodated. The Midland remained on the west side from Clear Creek until it had nearly reached Leadville.

40 | Scenic byway interpretive site

Granite Pullout: A Window into Transportation History

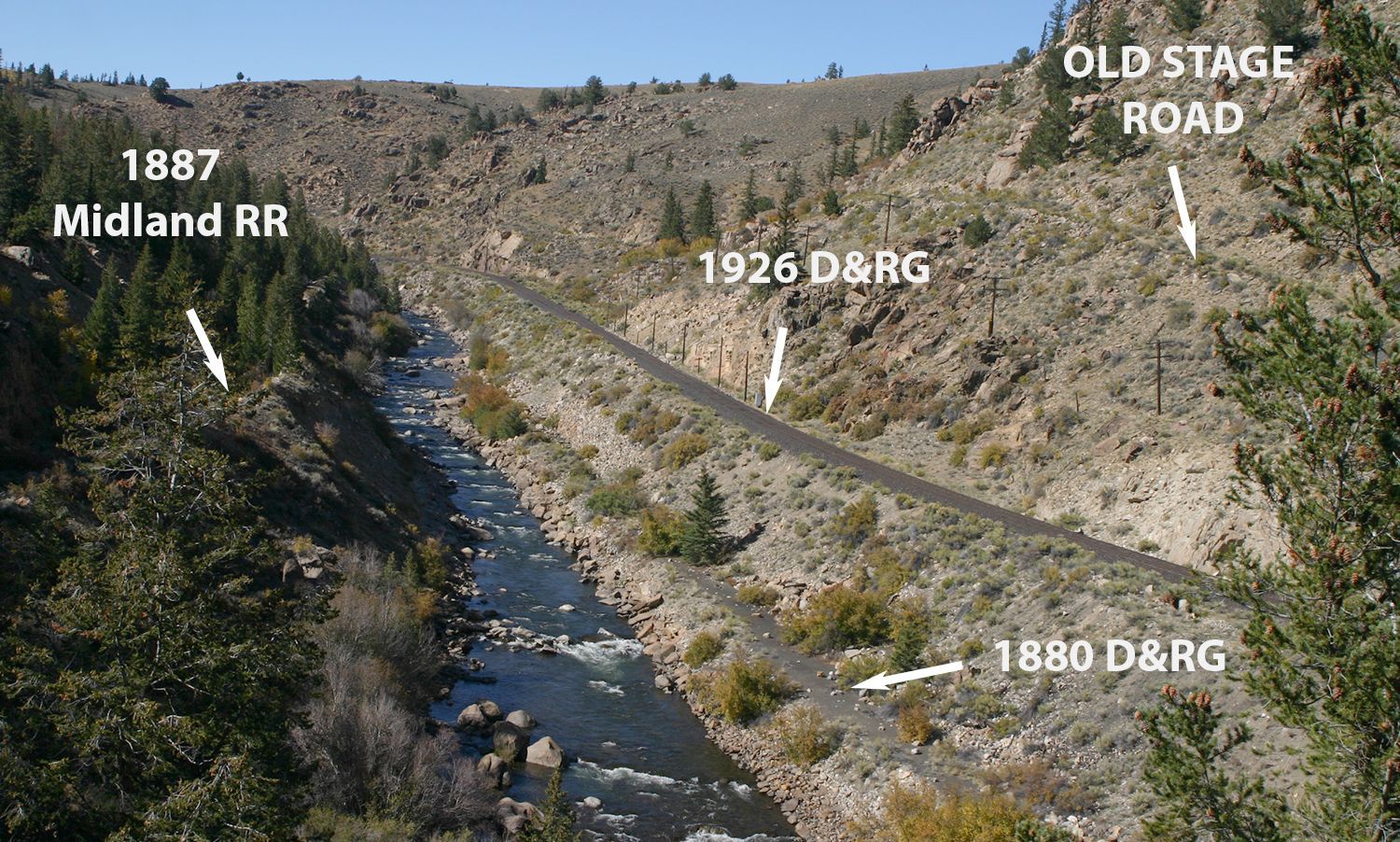

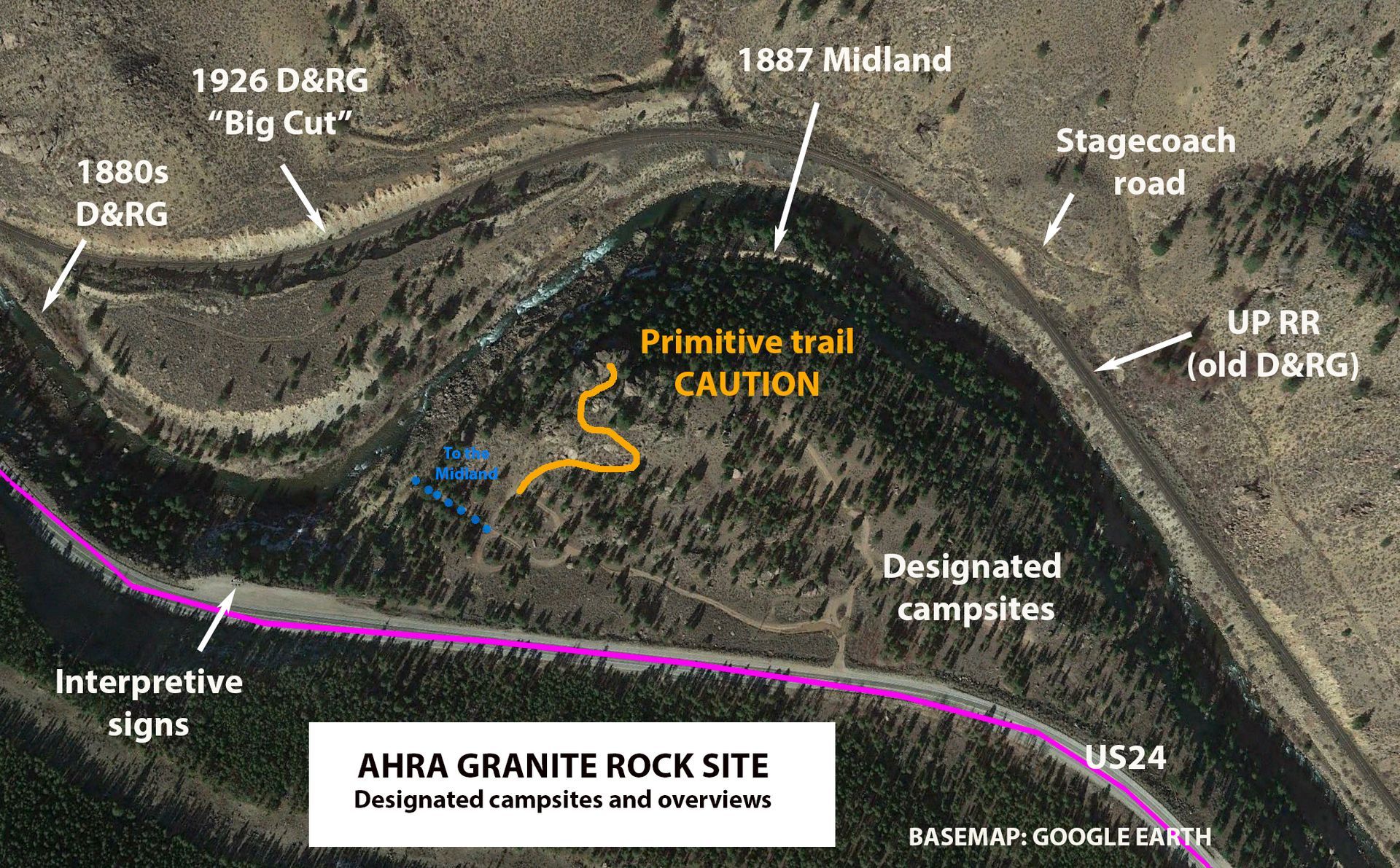

The Granite pullout and interpretive panels offer a unique vantage point to trace the evolution of travel along this stretch of the Arkansas River. Through interpretive text and images—both here and in this online brochure—you can visualize the sequential development of the stage road, the Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG) Railroad, and the Colorado Midland Railroad.

- The Earliest Route: The Stagecoach Road: High on the slope across the river, the old stage road marked the first major transportation path through this area. It’s unclear if it was originally that high or if the 1926 conversion of the D&RG to standard-gauge forced it higher.

- The D&RG’s Expansion and the “Big Cut”: When the D&RG upgraded from narrow- to standard-gauge, engineers had to excavate extensively—creating the “Big Cut.” A standard-gauge line required wider curves and a broader base, making it impossible to fit next to the river without this major modification.

- The Midland Railroad’s Late Arrival: The Midland Railroad, the last to be built, followed a different route on the west side of the river. It was cut into a bench above the river, below where the interpretive panels now stand.

For those eager to explore history firsthand, a gap in the fence at the east end of the pullout allows access to short hiking trails that lead into this historic landscape (see POI 41).

41 | Primitive interpretive trail

Exploring Granite Rock: A Unique Stage and Rail Overlook

The Granite Rock site remains undeveloped, but for cautious explorers and history enthusiasts, it offers a rare glimpse into the immense effort required to carve transportation routes through this rugged terrain.

⚠️ IMPORTANT: Be Cautious and Supervise Children

The area features steep drop-offs and uneven terrain, so caution is essential while exploring.

A Primitive Interpretive Trail

- A narrow, primitive trail winds to the top of Granite Rock, providing awesome views down into and across the river. From this vantage point, you can truly appreciate the sheer effort required to excavate the Big Cut—the massive trench created to accommodate the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad when it was upgraded from narrow- to standard- gauge.

Traces of Historic Routes:

- The original narrow-gauge D&RG line is still visible right next to the river.

- The old stage road can be identified above the Big Cut, where it once wound its way south, carefully staying high above the river.

- The Midland Railroad’s bench cut, though invisible from the top, lies directly below the steep drop-off on this side of the river.

42 | Granite bridge/town

A Rare Piece of Stagecoach History: Granite

Granite played a pivotal role in the mining history of the Upper Arkansas Valley. In the 1870s, it was a booming town of over 1,000 residents, rivaling Leadville in prosperity.

A Mining Powerhouse

Cache Creek District (West) – Gold extraction using high-pressure water hoses (placer hydraulic mining).

Hard Rock Mining (East) – Traditional deep-earth mining methods.

A Short-Lived County Seat

When Chaffee County was created from Lake County in 1879, Granite had the political influence to become its first county seat. However, in 1880, Buena Vista seized the title—quite literally, as officials from Buena Vista physically stole all county records from Granite (see POI 27).

A Decline in Fortune

By the 1890s, both placer mining and hard rock digging were exhausted, leading to Granite’s rapid decline. Today, only a few permanent residents remain, either retired or working outside the area.

A Surviving Stagecoach Hotel

Granite is home to the only still-standing stage station and Commercial Hotel from the Cañon City to Leadville stage road. Dating back to the 1870s, this National Register property stands as a unique relic of the stagecoach era. It is privately owned and not open to the public.

Respect Private Property

All properties along CR397 through Granite are privately owned. Visitors are asked to respect residents' privacy, including keeping pets under control.

43 | Denver and Rio Grande bridge

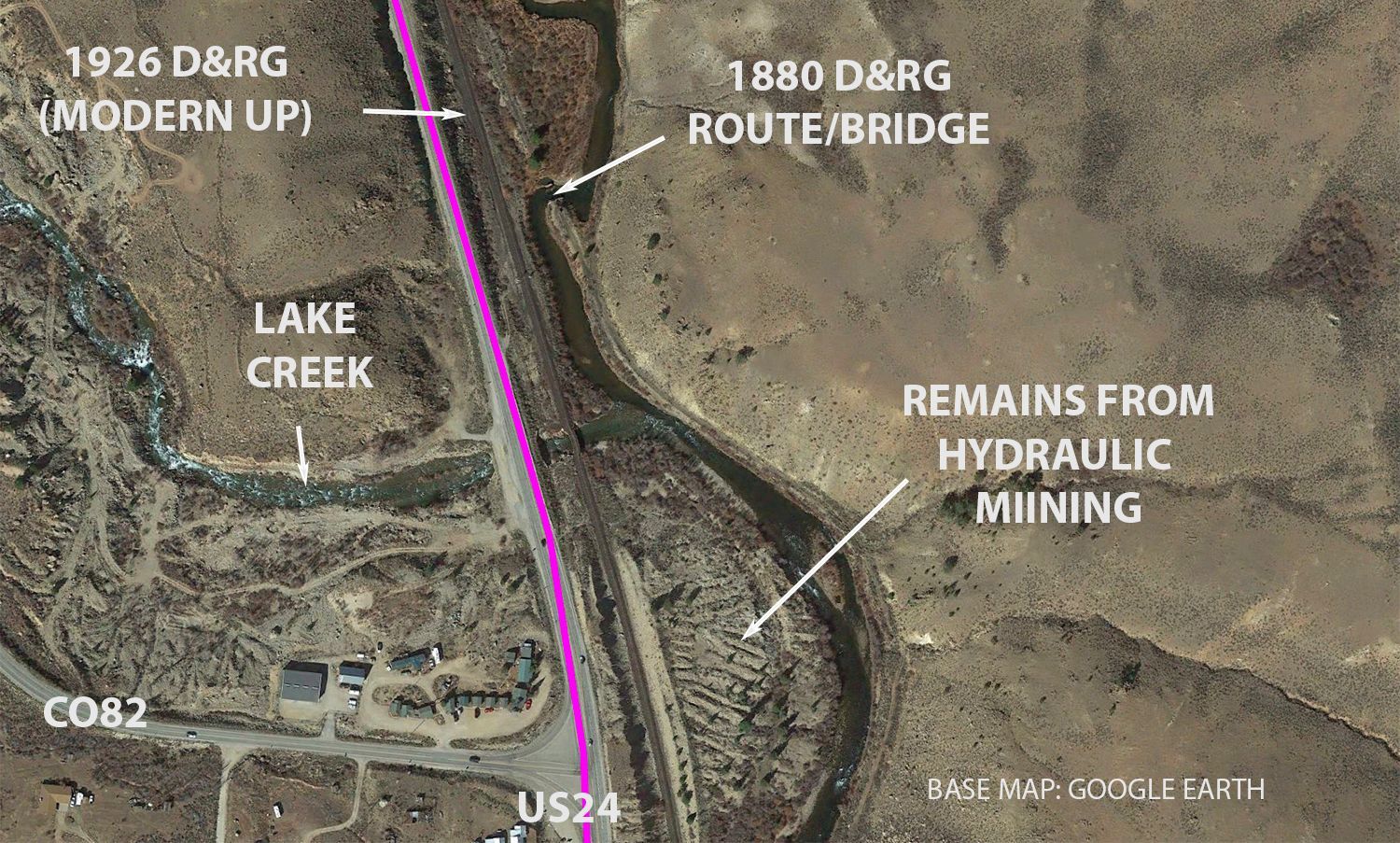

Bridge Abutments & The Legacy of Hydraulic Mining

Another crossing of the Arkansas

These bridge abutments visible east of US24 mark yet another necessary crossing of the original 1880s Denver & Rio Grande Railroad. At this point, the east bank’s increasingly rugged terrain made it nearly impossible to continue the rail line northward on that side. In 1926, engineers guiding the D&RG’s wider standard-gauge expansion had already decided to cross the Arkansas River even farther south, responding to the requirement for gentler turns. By contrast, the old stage road builders opted to stay along the east bank, and stuck there all the way to Leadville.

Rocky Remnants of Hydraulic Mining

The massive rock piles left behind by hydraulic mining are readily visible along this section of the historic route. Unlike modern reclamation efforts, few—if any—of these sites have been restored to their pre-mining state.

How Hydraulic Mining Worked

This highly efficient but disruptive mining method was widely used where terrain allowed for the construction of ditches and canals from higher-elevation streams. These channels provided high-pressure water, which miners directed through hoses powerful enough to blast away gold-bearing sediment, exposing river stones whose rounded shapes reflect an ancient history of being ground down and deposited by powerful ancient rivers, and subsequently covered by sediment eroding from the nearby glacier-carved high mountains.

The water and sediment mixture was channeled into intricate sluice box systems, where miners painstakingly extracted gold and other valuable minerals by hand. Essentially, hydraulic mining was a large-scale evolution of the handheld gold panning techniques practiced by hundreds of independent prospectors along the Arkansas River and its tributaries.

44 | Stage robber’s gravesite

An Isolated Grave & a Myth

This lonely grave has long been the subject of legend and speculation. The tale, told and retold for decades, speaks of a daring stagecoach robbery, a tragic revelation, and a secret burial—but how much of it is true?

The Legend

According to the long-standing story, a Leadville Undersheriff named Kirkham grew suspicious of a series of stagecoach robberies targeting southbound silver bullion shipments en route to the railhead in Buena Vista. Convinced that the bandits had inside information, he devised a sting operation, telling only a select few about an upcoming shipment and personally riding along with the stage.

As expected, a lone, masked bandit—cloaked and armed with a shotgun—halted the stage. When Kirkham and the driver refused to hand over the goods, the sheriff shot the bandit in the back as the figure attempted to flee. The shocking truth was revealed when the bandit’s disguise was removed—it was a woman, Kirkham’s own wife.

Stricken with grief and shame, Kirkham chose to bury her where she fell, avoiding the humiliation of returning her body to Leadville.

The Truth Behind the Tale

Recent research, however, has deconstructed the legend. There was never an Undersheriff Kirkham in Leadville’s historical records, and Jane Kirkham’s actual life is now better understood. She was married three times, with her final husband—a miner named Kirkham—bringing her to a now-forgotten settlement near this very spot.

How Jane truly met her end remains a mystery. Did she die of natural causes, or was she involved in outlaw activity, preying randomly on stagecoaches and freight wagons? The truth may never be known, but with it, one of the stage road’s most intriguing myths may fade into history.

45 | Arkansas River Community Preserve

Arkansas River Community Preserve (ARC Preserve) is Born

After a decade of collaboration among federal and state land agencies, Lake County officials, the Lake County Open Space Initiative (LCOSI), and the Central Colorado Conservancy, the Arkansas River Community Preserve (ARC Preserve) will officially open in 2025.

Acquisition of private lands for the Preserve occurred in multiple phases, funded through grants from Colorado’s GOCO program, the US EPA’s Natural Resource Disaster Assessment funds, private donations, and other sources. Detailed accounts of the Preserve’s history and 2025 status can be found on the Conservancy’s website, with a Management Plan, finalized in 2024, soon to be made publicly available.

A Vision for Preservation & Public Access

The ARC Preserve’s mission is twofold:

To protect the Arkansas River’s riparian corridor, including its critical fishery, wildlife, and natural resources;

To preserve significant cultural resources, including remnants of The Cañon City to Leadville stagecoach road; The original Denver & Rio Grande narrow-gauge railroad; The standard-gauge D&RG route, now part of the Union Pacific Railroad.

With its location providing the foreground viewshed of two scenic byways, the Preserve seeks to balance public recreational access with resource conservation. Lake County holds the public access easement, making it a key player in managing visitor access while ensuring long-term stewardship.

Relation to the Stage and Rail Historic Route

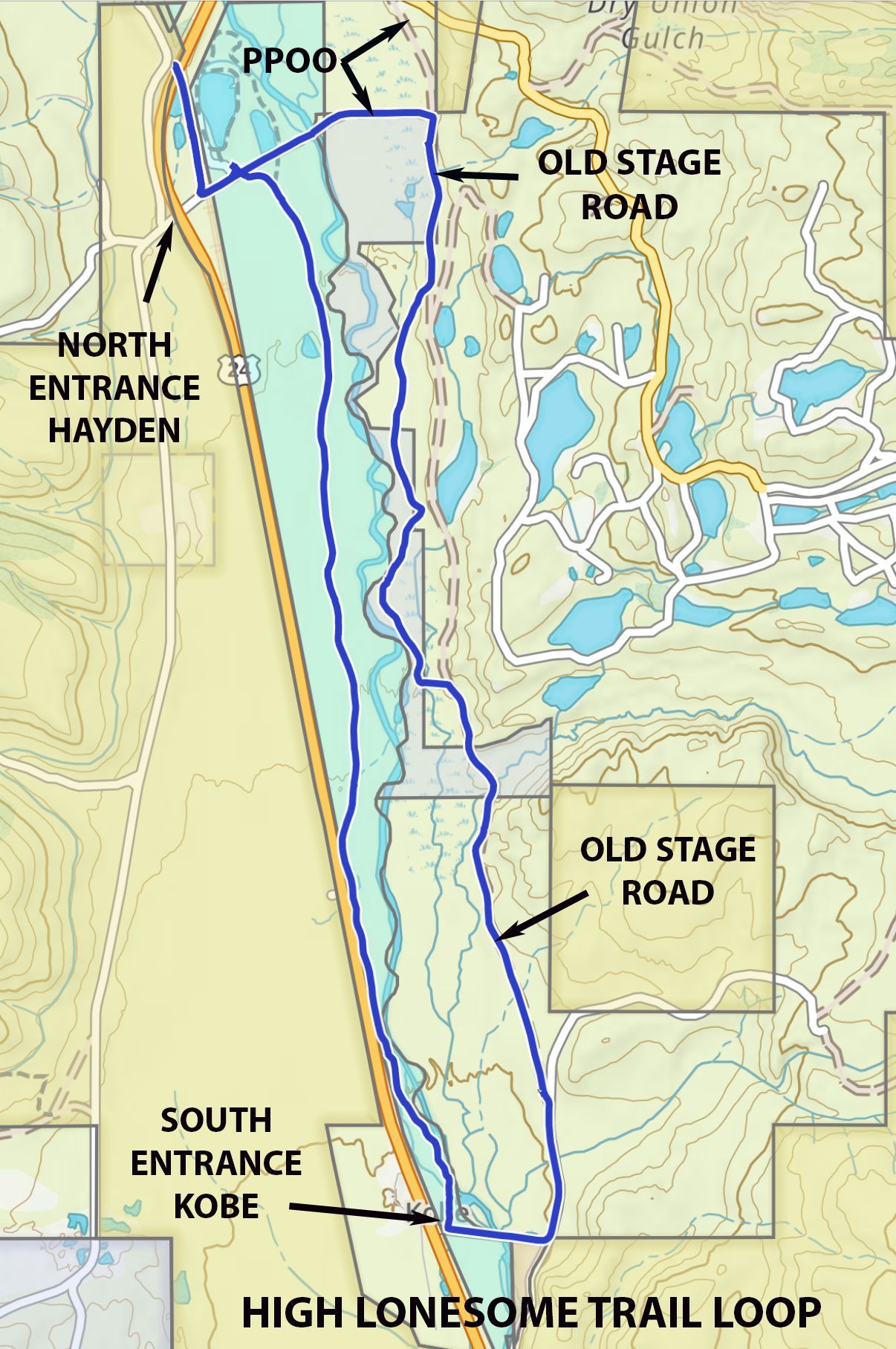

The 2015 Draft Arkansas River Stage and Rail Trail Master Plan envisioned the old stagecoach route becoming a publicly accessible trail stretching all along the east bank from north of Granite to Kobe and beyond. It was anticipated it would be open to non-motorized use, including pedestrians, horse riders and mountain bikes. This goal had not been accomplished prior to the 2022 establishment of the ARC Preserve; the type and extent of public use and access along the stagecoach road through the Preserve came under discussion as the Preserve’s principal planners, the Central Colorado Conservancy and Lake County developed the first edition of the Preserve’s Management Plan, completed in late 2024. Until certain constraints imposed by adjacent private property interests are resolved, the Plan concludes public access and use will be open but subject to certain limitations:

- Entry is currently available only from the south (or by crossing the river on foot);

- Since there is no entry or exit allowed at the Preserve’s north end, no through use of the old stagecoach road is currently possible;

- No decision has been made as to identification or improvement of the old stagecoach road or any other trail development or infrastructure;

- Public vehicle access is prohibited within the Preserve.

- Hiking and fishing are allowed, while the use of mountain bikes is still under discussion.

The 2024 Plan recognizes that natural resource conditions as well as public interest in recreation may change in future years. A commitment is made to collect and utilize additional data and public input in “adaptive management” to respond to those changes. The GARNA Stage and Rail Project foresees remaining an active stakeholder in how the Ark Preserve’s management evolves, and will continue to encourage public use of the stagecoach road as a through route.

46 | Hayden Ranch Headquarters

Legacy of the Hayden Ranch

The Hayden Ranch stands as witness to the vital role of ranching in the development of the Upper Arkansas Valley. One of the region’s earliest large-scale ranches, it was established in 1864 and acquired by the Hayden family in 1872, remaining under their ownership until the 1930s. Over the decades, the ranch adapted to shifting economic and market conditions, reflecting broader changes in the region’s industries.

Initially, the ranch specialized in hay production, supplying feed for its own livestock and selling to smaller ranches. However, with the rapid rise of mining in the 1870s and 1880s, the demand for hay surged as hundreds of horses and mules became essential in mining operations. A Denver & Rio Grande Railroad siding, built in 1880, allowed easy transport of hay to Leadville.

As mining declined in the early 1900s, so did the demand for hay. The ranch shifted toward cattle ranching, using the D&RG and the Midland Railroad lines for export. However, pollution from mine discharges degraded the quality of Arkansas River water used for irrigation, reducing the hay’s value and ranch productivity.

Around 1918, a Hayden family inheritor constructed a large barn with a water wheel powered by a diversion ditch from the river. An ingenious system of pulleys and belts powered a sawmill, hay baler, and other tools. (While preservation efforts to restore the water wheel were started, they remain incomplete.)

From Ranching to Conservation

Over the following decades, the ranch passed through various owners, including a failed attempt to develop a ski area on nearby Mt. Elbert.

In 1998, the City of Aurora purchased the Hayden Ranch, primarily for its water rights, with the long-term goal of building a water storage reservoir at Box Creek. After successfully transferring those rights for municipal use, Aurora sold most of the ranchland—minus water rights—to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). This shift led to the cessation of irrigation, meaning the land and its vegetation has returned to its natural, rainfall-dependent cycle. The land now managed by the BLM is important elk winter habitat but is also leased for cattle grazing, with the lessee employing a modern technique called virtual fencing to remotely control herd movement and ensure the best possible sustainable management of available forage.

Preservation & The Role of LCOSI

The pending purchase and reservoir proposal spurred creation of the Lake County Open Space Initiative (LCOSI) in 1997. This collaborative group, including representatives from Lake County, Aurora, federal and state land managers, and wildlife officials, has worked ever since by consensus to guide open space and conservation efforts here and throughout Lake County.

- LCOSI’s 2006 Ecosystem Management Plan, updated in 2019, has successfully advanced conservation efforts across Lake County, including advancing establishment of the ARC Preserve.

- Aurora donated 32 acres, including the Hayden ranch buildings, to a private preservation group, which began stabilization work.

- Eventually, ownership of this parcel was transferred to Colorado Mountain College (CMC), which planned to use the site for a Historic Preservation degree program.